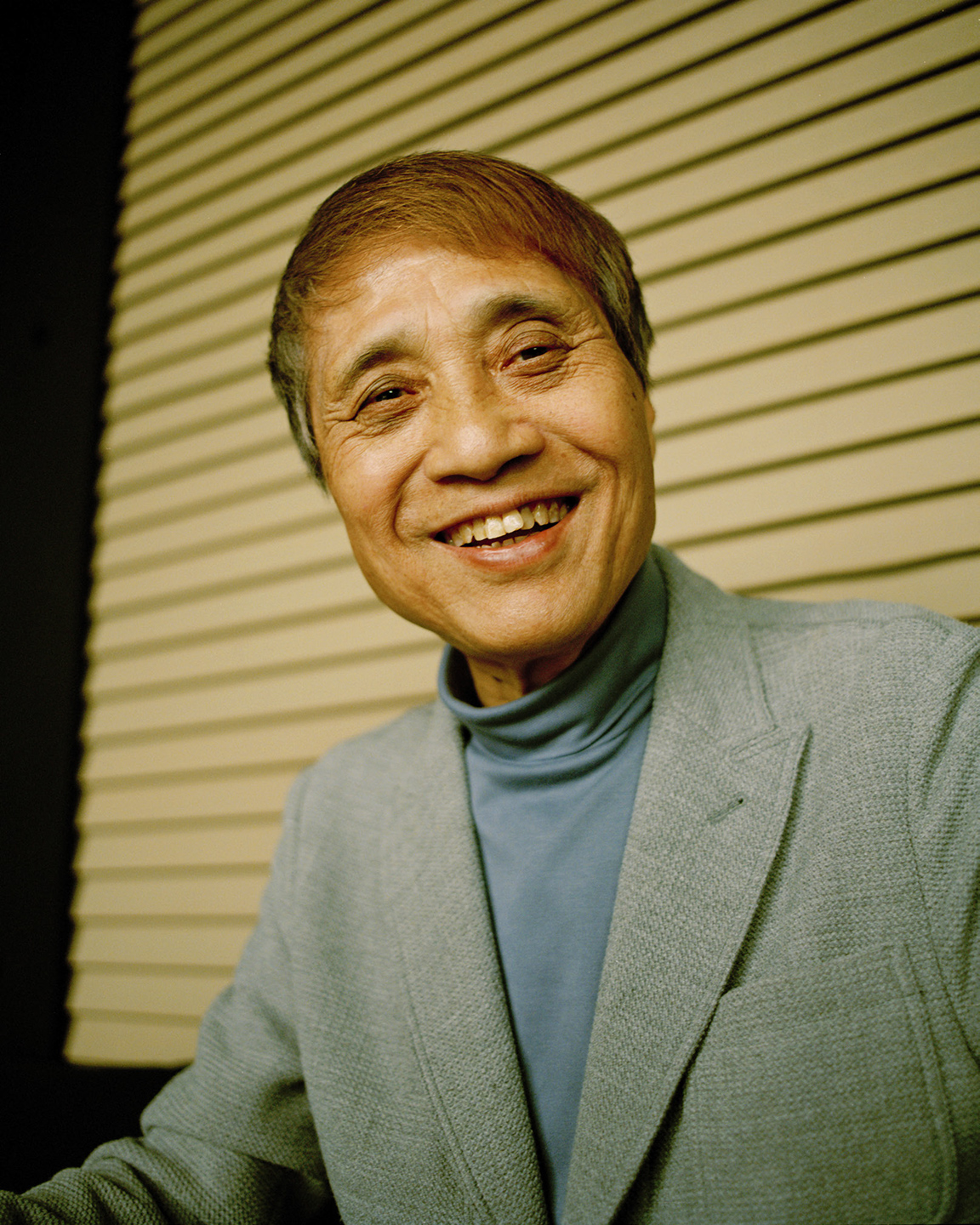

Breakfast with architect Tadao Ando

at Armani Silos in Milano

Conversation with Carlotta Tonon

Photography Andy Massaccesi

-

I visited his Milanese works and spoke to him on other occasions further down the line. Naturalness, rigour and pleasure in the form of icy grace are themes, and hopes, that are difficult to contemplate, intellectually. Yet still, the contrast between history and myth, the present becoming timeless and the fact that absence is undoubtedly often more imposing than presence are formulas that I cannot ‘process’. That said, here is the account of my breakfast with the master, before the opening of his exhibition at Armani Silos. I suspect that if I were to abandon speculation, the wisest and most honest answer would be his: “I felt in my bones”. This is it.

-

CTAt the risk of appearing intrusive, could you tell us an anecdote from your meetings? Which are the main elements that you feel are shared between your work and the work of Giorgio Armani?

-

TAWe share the same intensity and passion for our respective professions. I can’t imagine either of us retiring anytime soon! No matter your age, it is better to be an unripe green apple than a ripe red apple. To be unripe is to be youthful, to be naïve, to be energetic. When you have matured completely, you are no longer able to learn anything new or attempt something that might end in failure. To quote one of my favourite poems, Youth by Samuel Ullman, “Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul.”

-

CTWhat is your vision of fashion? Do you consider it an art like any other?

-

TAFashion designers are incredibly courageous, independent, and free-spirited. They are stepping forward all of the time. Architects must do the same. We must share the fear of challenging the unseen world. We are all human and we can be courageous but we cannot escape fear when taking risks.

-

CTThis exhibition covers 50 years of your life as an architect. What significance does a ‘synopsis’ of this kind hold in your view?

-

TAFor the last 50 years, I have consistently produced architecture. My career began with the design of private residences, then transitioned to commissions for larger commercial and community facilities. Gradually the scale of my work increased and I started to receive numerous opportunities to design culturally relevant buildings. Regardless of the scale at which I design, I consistently think about the methods in which architects and architecture can positively impact society. Whenever I make or create anything, my reoccurring struggle is to compose themes that can be orchestrated into buildings. For me, the entire design process has always been a challenge. However, it is the struggle, the repeated process of confronting difficult problems, that allows you to create new things. At this exhibition, I hope to appeal to the people of Italy through the exploration of my future endeavours and past accomplishments and to showcase my work and process to visitors to the exhibition. In high school, I was a professional boxer, so I am often asked about the link between boxing and architecture. Through boxing, I realised that perseverance and courage were necessary for survival. This realization has dramatically aided my education as an architect and is something that I still think about today. I did not attend university or receive a formal education in architecture. Even when no one would give me a chance, I still thought I could make it as an architect, I knew I would have to shift the existing method of thought in architecture in order to move the profession forward. The experiences I had in high school formed the basis of who I am today.

No matter your age, it is better to be an unripe green apple than a ripe red apple. To be unripe is to be youthful, to be naïve, to be energetic. When you have matured completely, you are no longer able to learn anything new or attempt something that might end in failure.

-

CTWhat is your typical day like? How do you live your life?

-

TAI never allow myself to be limited by my surroundings or upbringing. I have always thought that life is similar to a series of walls, each requiring more effort to break through than the last. I grew up in the downtown area of Osaka with little access to education or art. Before my career as an architect, I fought as a professional boxer. I was unable to attend university so I used the fighting spirit that I had learned through boxing and educated myself in architecture. This was very difficult but instead of thinking of it as a handicap, I chose to use it as a tool for motivation. When I was young, I would often pass construction sites in my neighbourhood. I was inspired by the workers, who would often skip lunch to ensure that the building would be completed with the utmost quality. It is this kind of passion that continues to inspire me to challenge myself with new endeavours. Over the years, I have pushed myself to create new types of buildings including Row House in Sumiyoshi, Rokko Apartment Complex, Naoshima Art Site, and Punta Della Dogana.

-

CTHow did your approach to design research develop? What are the most important emerging principles or visions?

-

TAWe live in a time when the world is changing dramatically at an incredible speed, with established concepts and values falling one after another. I am still unable to discern where we are headed or to foresee what kind of future awaits architecture. However, no matter how our means of creating architecture may evolve and no matter how architecture may change in appearance and form, I believe that architecture will always have the power to transcend its existence as a mere physical object and to act upon places and people. Moreover, I think that this power has the potential to bring new value to human society in ways beyond our imagination. Ultimately, the only way one can forge the future of architecture is by returning to the very roots of creation and reimagining architecture from its very origins. And one needs a fighting mentality in order to do this.

My home was a small row house, a dark place with little light and small windows. In the dim interior, I greatly appreciated what little light we received. I would often fill my cupped hands with light coming into my room. Since then, this is the type of architecture i’ve wanted to build.

-

CTItaly boasts several of your works, from commercial spaces to spaces for the arts and private residences. Did the impetus for working here arise from a specific path? Has it always been an occasion for happy interaction?

-

TAIt was through reading Domus magazine, founded by Gio Ponti, that I was introduced to the energetic work of many designers such as Alessandro Mendini, Joe Colombo, Marco Zanuso, and Ettore Sottsass. They were all producing exciting design in the form of furniture, architecture, and everyday objects and establishing their names in the world. During that time, as long as you were knowledgeable about art and architecture in Milan, you would be up to date with the most innovative design in the world. In 1965, when I visited Milan for the first time and encountered all the traditional and contemporary architecture, I was utterly mesmerised by the city. I will never forget the impact of seeing the Pirelli Skyscraper and the Salone del Mobile for the first time. Since Gio Ponti made the tower in 1958 and the Salone del Mobile began in 1961, Milan has further evolved into an internationally established design and culture mecca.

-

CTCould you tell us about your Japan?

-

TAI was born and raised in a traditional residential neighbourhood in downtown Osaka. My home was a small row house, a dark place with little light and small windows. In the dim interior, I greatly appreciated what little light we received. I would often fill my cupped hands with light coming into my room. Since then, this is the type of architecture i’ve wanted to build: architecture that values light and reminds me of the same feelings I experienced as a child. Nature, in the form of light, water and sky, restores architecture from a metaphysical to an earthly plane and gives life to space. Concern for the relationship between architecture and nature inevitably leads to a concern for the temporal context of architecture. I want to emphasise the sense of time and to create compositions in which a feeling of transience or the passing of time is a part of the spatial experience.

-

CTAre there any architects that you feel particularly close to, either through friendship or shared ideas?

-

TAThe first time I became aware of the architect Le Corbusier, I was in an old bookstore in Osaka. At that time, I was very passionate about life but my destiny still had to be defined. I was 20 years old and working part-time at an architecture design firm to make a living. I first laid my eyes on a portfolio of Le Corbusier in the art section of the bookstore. I immediately felt it in my bones. This was it. I couldn’t afford to buy it right away so I saved my money and bought the book about a month later. Then I read the book, page by page, every night. Even though my knowledge was not extensive enough to understand the intricacies of modernism, the contents of the book were utterly fascinating. Each page was beautifully laid out with close-up and wide-angle architectural photographs in addition to attractive plans and sketches. I thought, “I want to be able to design like this,” so I traced Le Corbusier’s floor plans over and over again.