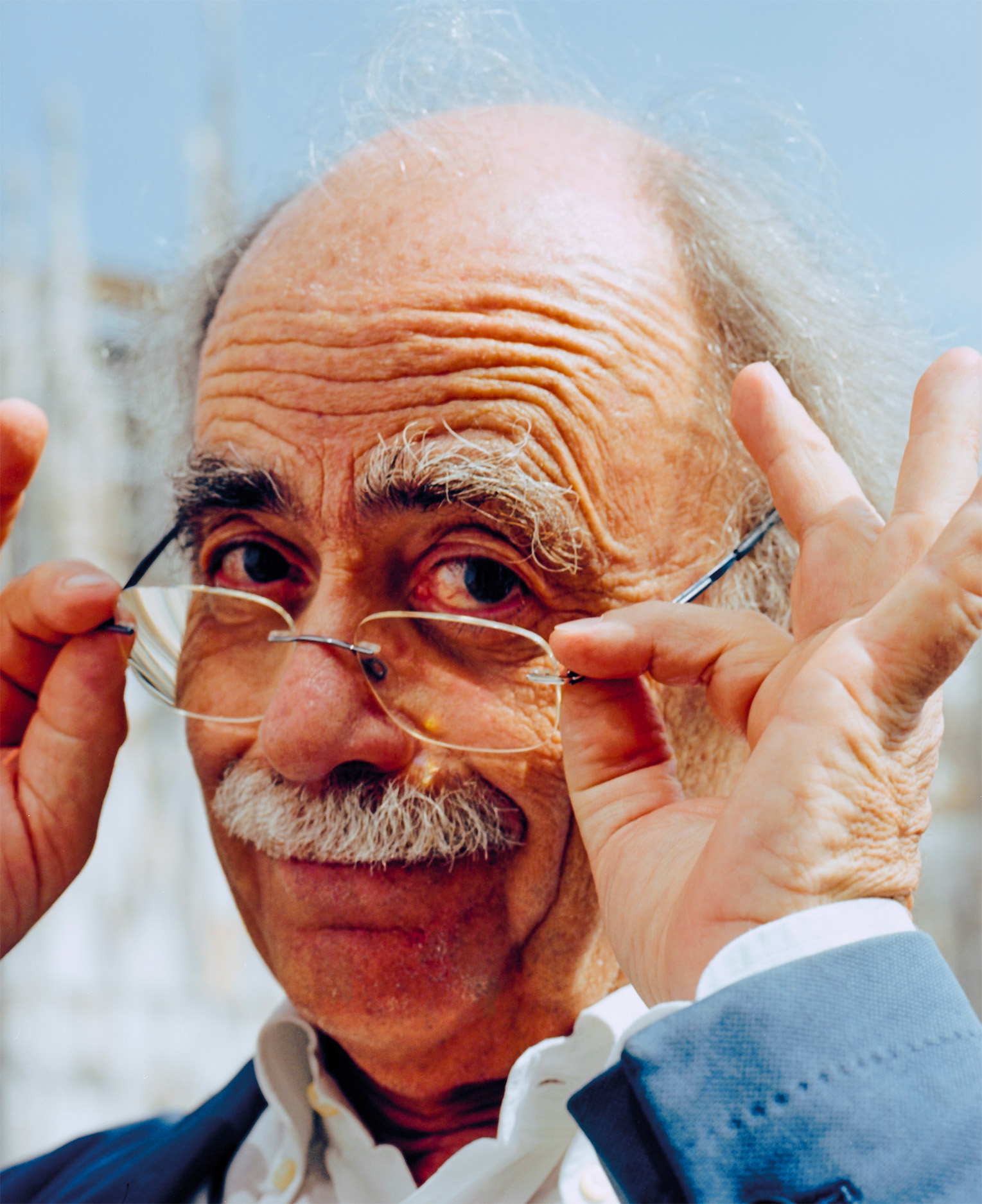

Lunch with Maurizio Nichetti

At Giacomo Arengario, Milan

Conversation with Carlo Antonelli Intro by Yara De Nicola

Photography Mattia Parodi

-

It is the first Monday in September and we are on the terrace at Giacomo Arengario's under the scorching sun to meet Maurizio Nichetti, the visionary director who in 1979 wrote and directed Ratataplan, the film that this issue of Alla Carta is inspired by and dedicated to. Today, Nichetti is the artistic director of the Centro Sperimentale, a lecturer at Iulm and the artistic director of the Visioni dal Mondo 2023 festival. We shoot a few portraits and then leave Carlo Antonelli, journalist, artistic director and film producer to take the reins of the conversation. It was less his qualifications and more his voracious intellectual curiosity and irreverence that inspired me to organise this encounter. During our shoot, Nichetti pulled out those masks so omnipresent in his films, which, when reviewed, seem almost crystallised in time: a cartoon that has never aged, just as Guido Manuli, co-director, drew in Volere Volare. Afterwards, as we’re waiting for the lift down to Piazza Duomo before going our separate ways, Nichetti refers to the interview with Antonelli as a Dadaist conversation. Here it is.

-

Ever since Yara called to ask me to interview Maurizio Nichetti (whom I had been thinking about for some time anyway, just because), I have rewatched or perhaps properly watched for the first time Ratataplan (1979) and Ho fatto Splash (1980), in particular, quite a few times. I was enchanted by what I saw as a kind of aesthetic hook between these vital decades—for Milan especially—that I remembered nothing about. Partly because I wasn't there. I was very young and I lived elsewhere. What I found was a sort of long-lost Italian style that seems to combine East Germany, slapstick of course, a certain all-round attitude to communication (which connects to a specific Milanese aptitude for uncategorisable geniuses—I'm thinking primarily of Pino Tovaglia), post-’freakism’/post-politicalism and of course the all-Italian trait of a mixing highbrow and lowbrow together when it comes to animation, later borrowed by the rest of the world. I know it is tedious to always be brought back to the starting point, without considering his later works, the essential role Maurizio had in the education of new talent at all the most relevant Italian film schools or his having invented and directed festivals of the most varied nature, but I quite selfishly got stuck in that specific space-time, partly because it vaguely reminds me of the most genuinely Italian cinema of recent years, urban-folk and the return of the lowbrow, Piero Marcello, Alice Rohrwacher...

-

I meet Maurizio at Giacomo Arengario, a restaurant at the top of the Museo del Novecento, which I had also forgotten about, lost in a distant fog of absurd dinners with absurd people. Nichetti is exactly the same, he bears no signs of particular suffering. He has been with the same woman since those early years and he seems to have lived a serene life. Not bad. I don't know why but in rewatching his first film, my rapacious gay gaze noticed his unexpectedly lean physique and a nicely protruding bum as well as a nice elasticity overall, especially when jumping and running. Entirely nonchalant, I mention it immediately. “I used to do athletics, the hundred metres. And then mime at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan (Ed. another institution and fundamental local cultural-chic tastemaker), for almost eight hours a day, with somersaults too”. I realise that my current unjustified chastity has led down paths that should never be taken. For any reason. I start again. There was a central political caesura in Italy around 1977, in Bologna in particular, but throughout the country. After ten years of street demonstrations and extra-parliamentary politics on all sides, a slice of the protesting side broke away and chose the path of irony, albeit still political. Is that correct? “Oh yes, the Indiani Metropolitani (Ed. Metropolitan Indians), as they were known at the time, used to say, ‘a laugh will bury you’", erupts 100-metre-runner Nichetti. “I had Ratataplan at the end of the 1970s. I came from the student movement at the Faculty of Architecture. It had all been serious stuff but I was leading a double life. I used to go to demonstrations but I liked theatre and comic things (in 1974 I founded a mime school, which still exists today: Quelli del Grock) and I worked as a director in advertising.” My blueberry salmon tartare arrives, while he has ordered a fish. “When the attacks started, they were attributed to both right and left. But when people die you can't stand there and create political division. It was a city—Milan—where you’d get it if you dressed a certain way, from one side or the other depending on your style. The strategy of tension, the bombings, the kneecappings—none of that belonged to us. As a generation that grew up in '68, we wanted to change the world for the better. That wasn’t what we had in mind. It was a war, the years of lead. The woman who would become my wife—we were already together—happened to be passing by Piazza Fontana as the bank exploded. It was like living under bombardment. There was the silent majority and the extremities: Nar and the Red Brigades. In 1976/1977, the Indiani Metropolitani with a laugh finally said, ‘We’re fed up’”.

-

Your two films of those years touch on experiments in kinship and non-Euclidean living. “All my friends lived in communal spaces. The house in Ho fatto Splash was Angela Finocchiaro's house (Ed. a popular actress of the time and great friend) where she lived with other girls. In that film, a couple leaves their baby to the three roommates and it’s all true. The couple are still away to this day. They are in Portugal, they have travelled all over the world, they have made a little money go a long way by travelling via the cheapest means, on cargo ships and planes that were the forerunners of low-cost air travel. They would send us letters with their stories.” From Giacomo Arengario’s incandescent terrace, I can see a million tourists piled up in Piazza del Duomo. There is no room for anyone else. “You were saying about my Milan looking like the DDR?” Maurizio brings me back to the room. “I don't know, but it is definitely a city of poor people, living in popular housing, struggling to make ends meet. I chose the metropolitan city, the suburbs.” You had this sombre background and then splashes of colour everywhere. “Remember that I was a mime, a clown. Fortunately, some people refused to live in the grey.” How did your first film come about? The usual stroke of luck? You sent the unsolicited script to legendary producer Franco Cristaldi and... “The true story is that I had sent it to him the year before. Silence followed. Only much later, one evening at dinner, did he confess that he hadn't actually read it. It all happened because the co-producer, Nicola Carraro, saw me dancing in Ischia, at a festival, in which Bruno Bozzetto was presenting Allegro non troppo (1976, we'll come back to it), which I had written and much more, and he had been unable to attend. I had to get a laugh on the dancefloor naturally.” I rewatched that film again too of course. It is a sort of Italian Fantasia, with a very strange vibe that draws from the historical avant-garde and from a certain idea of comics that would now be shelved under the label ‘sophisticated graphic novel’. A taste that can be spotted, for example, in the girls' flat in Splash, even in the decor of the wardrobe. “They called me to ask if it was a Balla or an original futurist piece. We had copied it obviously, you used to paint things yourself back then.” Let’s get back to Allegro. It brought together an entire generation of Italy's best illustrators and animators, all of whom were based in Milan. They were the sum of many skills and they each got an episode. Bozzetto drew the Slavic dance, to give you an idea. You had early 20th-century avant-garde fractures, Dino Buzzati, the Beatles of Yellow Submarine. Your observation of original animation, of certain traits and colours... “I never made these convoluted reasonings, they were all just ideas that came to us.”

-

Stubborn to the end, a few days later I called Bozzetto: 85 years old, fit as a fiddle and as real as they come. “I can confirm that this theory is all of your own making. When I was young I made a film based on a drawing I did while talking on the phone, two mountains with a castle on top. So much for layers of references. What was my life? I was making films; I didn’t even know what was going on in ‘68. Once I went to America and they asked me if I went out much. Please. I read books, so many books, from Lawrence to Ethology to Pavese to Hemingway... Do you want to ask me about Nichetti? Maurizio was fundamental for live action. He obviously had in mind Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, black and white, which I then put in the ‘breaks’ for Allegro because I wanted to enhance the colour of the animations... What am I doing now? I'm working (Ed. there's that stubborn Milanese trait). I'm making three short films that I'm going to merge into one. All in defence of animals and against man. I don't see any hope, we are heading for the extinction of our species. We have been on Earth for 200,000 years and that's far too many. We are destroying our home bit by bit. We are stupid. There is only a minority of wonderful people who have done wonderful things. Me? I consider myself as someone who does no harm and no more. Maurizio? A brilliant guy, full of ideas, hugely valuable. Ratataplan was a wonderful film. I admire him so much. As much as I admire the new generations in whom I place great hope, they are still learning and shaping themselves. It is no coincidence that my creed when working is something a primary school child said: drawing is an idea with a line around it. Perfect. Through it all, I have the Ratataplan music in my head for days on end. I see Nichetti again. “Well, Giorgio Armani used it for one of his fashion shows in 1979 or 1980, for one thing.” You are eminently practical and yet you've always operated within an interstice between real and unreal, between live action and artificial. Could this be precisely why you are so comfortable with AR and VR, and beyond? It's as if, via a quantum leap in time, this present doesn't surprise you at all. “I feel more stimulated by new technologies and this has been the case for a long time, since Allegro in fact. These are the experiments that pull me in. I certainly haven't missed the cinema in recent years.” Do you take medication? “I’m against it.”