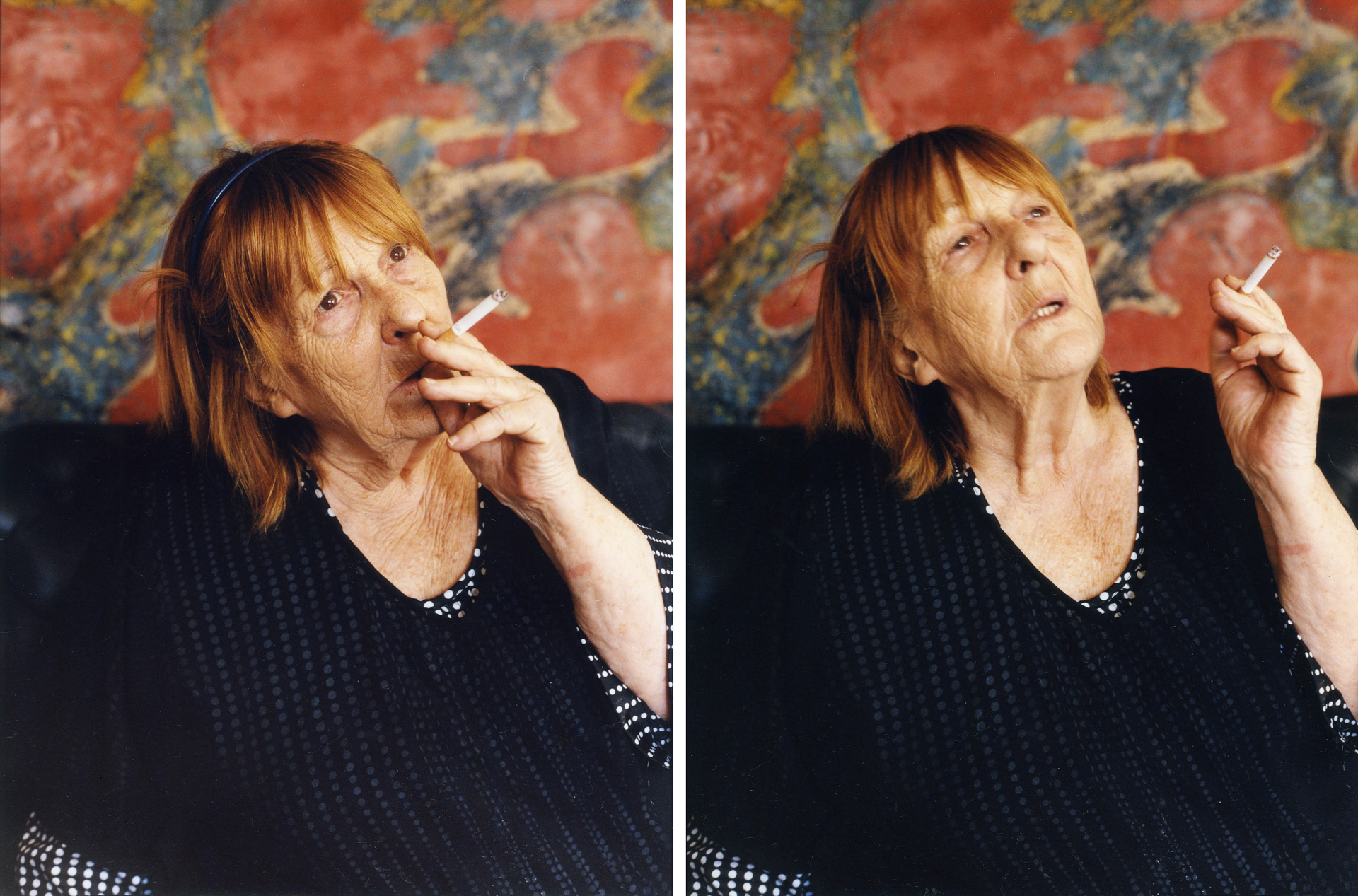

Breakfast with Letizia Battaglia

Breakfast with Letizia Battaglia

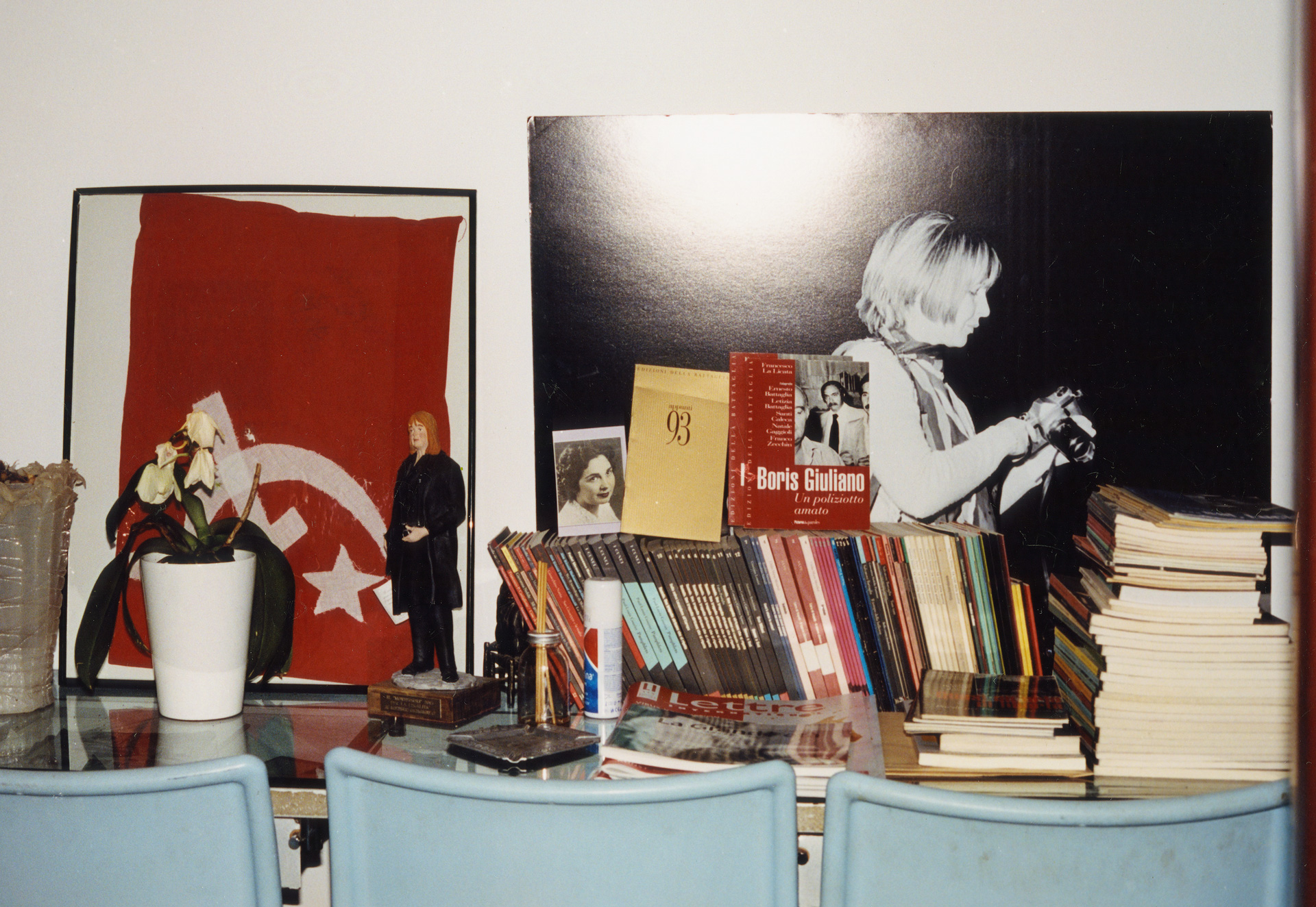

At Letizia’s home in Palermo

Conversation with Gabriele Miccichè Photography Jonathan Frantini

-

A woman born into Palermo’s middle classes in the Sixties, when Palermo was almost a normal city. She was unsettled, despite having three children already. Family life suffocated her. So she began to sell sanitary products door-to-door.

-

Quite customary at the time. Then she turned to Vittorio Nisticò, editor in chief of L’Ora newspaper. She was looking for a more fulfilling job. It was 1970. The journalist Mauro De Mauro had only recently passed away. The city was beginning to adopt the tragic role that it would uphold for the next 30 years. The L’Ora newspaper was a mine of talent, a miracle of independence and quality in a city that was interested in neither. Letizia began to write. She wrote about the nomads, following the circuses and peddlers as they passed through.

-

Then she moved to Milan with Santi Caleca, who began taking photos in that period. She continued to work for L’Ora. “I lived on Corso Concordia and I earned 80,000 lira a month. Oreste del Buono lived in the same palazzo as me.” With Santi she began to work for ABC and Le Ore which were considered – and were essentially, especially the second – pornographic newspapers. “Those photos would make us smile nowadays.” It was the Milan of Dario Fo, Franca Rame and Mario Capanna. She frequented women’s centres. The communist magazine Vie Nuove asked her to work with them. And so her career in photography began. “I remember the audience with Pasolini at the Press Association for the presentation of Le mille e una notte. They destroyed him.” It was there that she took one of the most intense photographs of the poet and director. She began to frequent the world of law. “I would photograph court cases. I was attracted by the theatrics of the characters you found in the courts. They gave Shakespearian performances.”

-

In 1974, she returned to Palermo to become head of photography at the newspaper. “Working for L’Ora in those years was a great responsibility. We had to compete against the Giornale di Sicilia, which had far more resources, with only quality and intelligence. One of our techniques was to stay tuned to the police radio.

-

We had to do more, be more creative, have more ideas. I didn’t celebrate New Year’s Eve for years. My job was to be at the newspaper listening to the news that came in from the police station or to photograph other people celebrating.

-

They were the Weegee years. “Can I write that?”I ask her. “Of course, it was back then.” I should clarify something. Two great photographers from Palermo were active in those years: Enzo Sellerio and Ferdinando Scianna. Two refined photographers from Cartier Bresson’s great school of neo- realism. Their most important photographs show religious festivities, markets or the children of Palermo. It was a Palermo that was fast disappearing and which urgently needed to be immortalised in their shots. Letizia, on the other hand, was with Franco Zecchin – her companion for 18 years – who was a photojournalist to the core. A photojournalist who shot the city as it really was. With its “dead and wounded” (this the trump card of Palermo’s paperboys as they sold papers at the traffic lights). It would be more precise to say dead and murdered. There were lots of murders in Palermo, especially from the Eighties onwards. Police, magistrates, mafia rivals and politicians. Without the photographs of Letizia Battaglia and Franco Zecchin, it would be impossible to understand what Palermo was like back then. The terrifying years of carnage. Palermo was a schizophrenic city in the Sixties and Seventies. It was the swinging, creative and experimental Palermo. Home to the first compositions by Stockhausen, a city that produced free theatre of the highest quality. That experimented with brand new politics. It was the Palermo of Mario Mineo, Michele Perriera. It was also the city that saw the debut of one of the country’s most successful publishing companies. The Sellerio publishing house was created by photographer Enzo and wife Elvira with support from Leonardo Sciascia, who lived in Palermo, anthropologist Nino Buttitta (son of Antonino, the poet of Bagheria) and archeologist Vincenzo Tusa.

There were lots of murders in Palermo, especially from the Eighties onwards. Police, magistrates, mafia rivals and politicians. Without the photographs of Letizia Battaglia and Franco Zecchin, it would be impossible to understand what Palermo was like back then. The terrifying years of carnage.

-

But at the same time, it was the city that just left one of Europe’s largest and most spectacular historic town centres to fall into ruins. It was the city where construction ran wild. A city where people were shot, blackmailed and extorted. A city destined to become a nightmare.

-

Letizia Battaglia is the city’s most coherent representative. Her camera (a Pentax K1000) a testimony to what was happening on the streets of Palermo, what better-known photographers had no desire, or stomach, to capture.

-

The L’Ora newspaper closed right around the time of the attacks on Falcone and Borsellino. Letizia had already begun another career however. After a stint on the Palermo city council on Orlando’s team, she was elected as a regional councillor for the Green Party in 1991.

-

“I gave everything to politics. Being a councillor was the best experience of my life. I found a passion inside myself that I hadn’t believed possible. The sensation of being able to offer law and justice. Not so much in the sense of enforcing the law, although that as well, but the certainty of doing the right thing. I was occasionally accused of being anticlerical. I have never been anticlerical but I was, and I am, against anybody who denigrates or oppresses the beauty around us. I am against abstract rules. Against systems – like Palermo – that ignore that beauty. It was the happiest time for me, more fulfilling than taking beautiful photographs.

-

Letizia has always been a ‘militant’. It’s in her DNA. She loves the theatre, she took part in all’Apocalypsis cum figuris by Jerzy Grotowsky and in Teatès, the theatrical project by Michele Perriera, one of the founders of Group 63. “A wonderful person, like Ludovico Corrao the psychoanalyst. The sort of maestro that stays with you, how can you live without them?” She met Pina Bausch, with whom she worked during the long period that the choreographer lived in Palermo.

-

Letizia’s photographs are not merely a narrative however. Her images cover all fields. The photo of a 10-year-old girl holding a ball is one of the most iconic images of the 20th century. It was hard personal experience that inspired her love for this subject. “I grew up in Trieste because of my father’s work”. At the age of 10, she returned to Palermo with her family. She was a free child who had grown up on the streets, quite normal back then. But they were ‘friendlier’ streets, with less cars and less dangers than now. The worst that might happen was bumping into a flasher. A harmless imbecile in most cases. But suddenly in Palermo she discovered that you couldn’t go out alone. She was becoming an adult. It wasn’t proper to go out alone. She felt a strong and painful sensation. “I felt like I was dying. It felt like my life was over. I couldn’t wait to leave home.” And she duly got married just after turning 20.

-

I like this story because it helps us understand how all her photos reflect a precise personal experience. Her experience of photography is violently emotional. “There are moments in which I am overwhelmed by emotion. I genuinely obsess over photos. They help me forget the dead and murdered. Then when I’m developing the proofs in the studio, I see the photos and they all look awful. But then comes the selection. I am excellent at selecting. I know how to look at other people’s photos. I knew instantly that Koudelka, who came on a camper trip through Greece and Turkey with Franco and I, was outstanding. I also love many female photographers: Sally Mann, Francesca Woodman.”

-

In recent years, Letizia has begun a project that has seen her repropose some of her photographs in different contexts: photomontages, constructions of repeated photos. I ask what her reasons are.

-

“You need to continue to destroy in orderto know how to create. I am inspired by the Molly Bloom monologue in Joyce’s Ulysses and even more so by Canto 81 by Ezra Pound. I see that composition as the basis of my creative life. When he states “but to have done, instead of not doing” - she recites from memory – and takes on vanity: it’s like an invitation to tear up the canvas. To always start again.”

-

Pull down thy vanity, I say pull down.

-

Learn of the green world what can be thy place

-

In scaled invention or true artistry,

-

Pull down thy vanity…

-

It’s a good way to close this article. Maybe even the best.