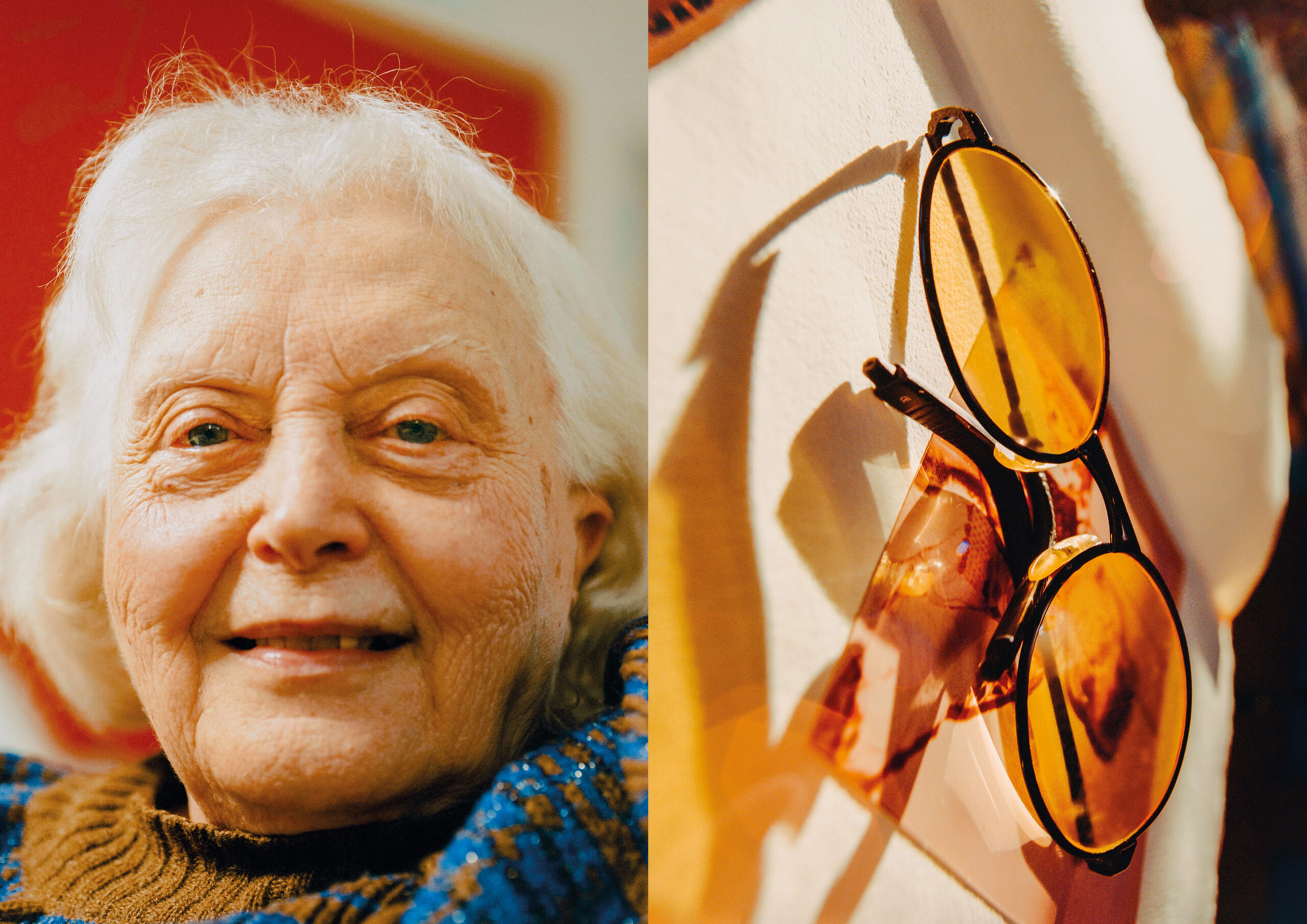

Coffee with Tò Ma Sò Binga

A conversation between artist Bianca Pucciarelli and curator Luca Lo Pinto Photography by Mattia Parodi

-

Bianca Pucciarelli was born 92 years ago in Salerno. Although she is recognised today as a seminal figure in visual and sound poetry, she does not consider herself an artist but a person who plays with art. Play, curiosity, and poetic militancy are vital ingredients in her work. Her 1971 debut on the art scene took place at the peak of feminist fervour and, half-jokingly, she decided to take on a male name inspired by Marinetti, the father of futurism: Tomaso Binga. Using different languages (photography, painting, performances, and video), Binga continues to experiment with language in its written and oral forms, making the word and the body one.

-

LLPIn some of your interviews, you affirm that the moment that changed your life was a Piet Mondrian exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern Art. You and your husband Filiberto Menna had moved from Salerno and I imagine the shift from a small southern town to a metropolis like Rome had a powerful impact. I'm curious to know how that exhibition inspired you to become an artist and Filiberto, who until then had been a doctor, to become an art critic. If you had never left Salerno, perhaps none of this would have ever happened.

-

TBNone of it would have happened. We’ve asked ourselves this several times. Coming to Rome and having this first shocking impact changed our lives. We began to visit galleries that we could never have gone to in Salerno because there weren’t any at the time. I've known Filiberto since we were kids because we lived near each other, although there’s a five-year age gap.

-

LLPWere you together when you attended the Mondrian exhibition?

-

TBNo, it was actually in Rome that we met again and started dating. I had left Salerno to teach but we exchanged letters, commented on the books we were reading, and so on.

-

LLPWhat was it that struck you about that exhibition?

-

TBIt was something completely new for us. It wasn’t figurative art, which was our artistic reference point. The concise, synthetic result of the absence of any figuration had a profound impact on us.

-

LLPWhat have been the happiest and saddest aspects of your adventure in art, from the very beginning to today?

-

TBHaving always been self-critical and self-deprecating, I’ve always approached everything not with the seriousness of art but with an attitude of play. So while there were some unpleasant episodes, I was never bothered because I didn't want to become an artist. It was a combination: I didn't take myself seriously and I played with art. Even today, I don't consider myself an artist but somebody who plays with art. Having said that, I do carry out extensive research, it stimulates me to find the key to change.

-

LLPWe are witnessing the ever-greater professionalisation of art in every role.

-

TBOh yes, there’s a real lack of self-irony.

-

LLPI have the impression that you have always resisted the self- referentiality of art. You say that you frequented above all the world of poetry and theatre, demonstrating a fascination for other languages. Your performances are almost cabaret in dimension—in a positive sense, of course—whole your artistic references are closer to conceptual art and visual poetry, both dry languages devoid of the irony that defines you.

-

TBWe did cabaret poetry for a while. We would go to various clubs and recite these poems.

-

LLPWere these art spaces?

-

TBWe did it everywhere. There were groups of us and we went around reciting poems. People recited poetry everywhere in the 1970s, even on buses!

-

LLPIt was poetic militancy instead of political.

-

TBYes, there was a real poetry explosion.

-

LLPWhich poets did you hang out with? Did Amelia Rosselli come to the evenings you organised at home with Filiberto?

-

TBOnly once.

-

LLPVictor Cavallo?

-

TBNo. We had a different crowd, more theatre oriented. We were very good friends with a theatre critic, Achille Mango, who taught in Salerno and followed experimental groups such as La Gaia Scienza.

-

LLPReturning to your influences, your playful and biting tone recalls the spirit of the Dadaist Cabaret Voltaire or Futurism. And it’s not by chance that you choose to call yourself Tomaso in homage to Filippo Tomaso Marinetti. There was a real mixture of languages In the historical avant-garde (music, theatre, cinema, and literature). The concrete and visual poetry of the 1960s was at a level of linguistic deconstruction similar to conceptual art...

-

TBVisual poetry has been my bread and butter much more than conceptual art.

-

LLPThe performative dimension plays a fundamental role in your work.

-

TBYes, per-forming.

-

LLPIn much visual poetry, the formal character is favoured over the semantics of language. A bit like your desemantic writing, which we can read as a simulacrum of writing.

-

TBIt's an image of dilated writing where the meaning remains because while you're writing it, you know what you're writing, but when you go to read it again it's impossible to decipher.

-

LLPThen at a certain point you abandon pen and paper and move on to the voice...

-

TBYes. There was a phonetic continuation to it because I was interested in this mad overlapping or dilating of voices. The most important thing was repetition. Repetition of the same word, phrase, or syllable. Right from the start, I would recite the poems in my own personal way, just for fun as usual. They resembled the chants of children playing and repeating the same words. I loved the ones sung in rounds.

-

LLPAnd what about Rome? I’m interested in understanding how you’ve seen the city and the art scene change from the 1960s to today.

-

TBThe biggest change happened back in the ‘70s, influenced by the fact that most people had lived through the war and therefore there was this sort of liberation. War changes not only landscapes but also people. We realised that it was necessary to bring about a change and break down all these taboos, especially from the female point of view. The total liberation of the 1960s was purely female. Women became aware of themselves and the qualities they had. We could not go on living as we had up until then.

-

LLPThe personal is political!

-

TBExactly.

-

LLPYou leveraged poetry with a less aggressive and angry approach than feminist collectives or female artists such as Cloti Ricciardi who forbade men from entering the Incontri Internazionali.

-

TBYes. I've never been part of any groups.

-

LLPHow do you view feminism today? There is renewed attention on female figures who have been forgotten by history. Yours is a case in point.

-

TBFeminism is a bit watered down now. It is very different from the aggressive feminism of the past. It no longer makes sense to use the word, really. Perhaps we should invent a new one.

-

LLPAbsolutely.

-

TBBack then it was an awakening, a revolt. Today, a nostalgic memory.

-

LLPIn recent years, we have witnessed the historicization of the feminist movement in the artistic context with past exhibitions and works being shown again. The issue has become institutionalised. The last Venice Biennale even went down in history as the edition with the highest female participation. This is an important fact but one that must not obscure the value of these female artists, otherwise there is a risk of exploitation.

-

TBThings must be done but not in the past tense.

-

LLPSomething else I wanted to ask you about is your relationship with the medium of the book. In the field of visual poetry, magazines, and books were media used by artists as more accessible and functional alternatives in terms of distribution. Are you interested in the book as an instrument?

-

TBI have produced some artist books but I don’t have a great passion for it. If the artist book is a work of art in itself, why call it that? It is an art form that uses books.

-

LLPWhat is it that fascinates you about alphabets?

-

TBA lot of my work is based on alphabets. The alphabet is a sign that is incorporated into the person. It is the body of the word. Starting from this point, I made the alphabet with my body: mural, primordial, officinal... I recently found a baroque alphabet that I want to work with.

-

LLPGiven the name of this magazine, could you tell me about a food- related project you have worked on?

-

TBIt was a table setting. I used a pen and pencil as cutlery and I glued my writing to the bottom of plastic plates. I also wrote a diet poem.

-

LLPTell me about your historic appearances on the Maurizio Costanzo Show.

-

TBIn 1995, I sent a tape to the editorial office and they called me back a week later. I went on the show loads of times. My debut was funny because I was reciting a poem and the audience started groaning. So, to spite the public, Costanzo made me read another one from a list I had sent him and he chose: Ed io non te la dò! [Roughly translates as ‘You won’t be getting lucky with me!’, Ed.]. It was a riot. People stopped me on the street after the first night.

-

LLPHave you noticed that we’ve talked all this time and I still haven't asked you a question about your name?

-

TBYou haven’t! The name has actually undergone changes... I'll give you a preview of the latest one: Tò Ma Sò Binga!

-

LLPIt is very special to see how much joy you take in being an artist regardless of acknowledgment or even forgetfulness towards your work. You have always carried out your research with great coherence and positivity. You don't suffer from the repressed condition which so many artists do. You are always looking ahead and experimenting with curiosity.

-

TBI've always liked finding something new to do. Whenever Filiberto left the house in the morning, he would always say: “Archimedes, what will you invent today?”