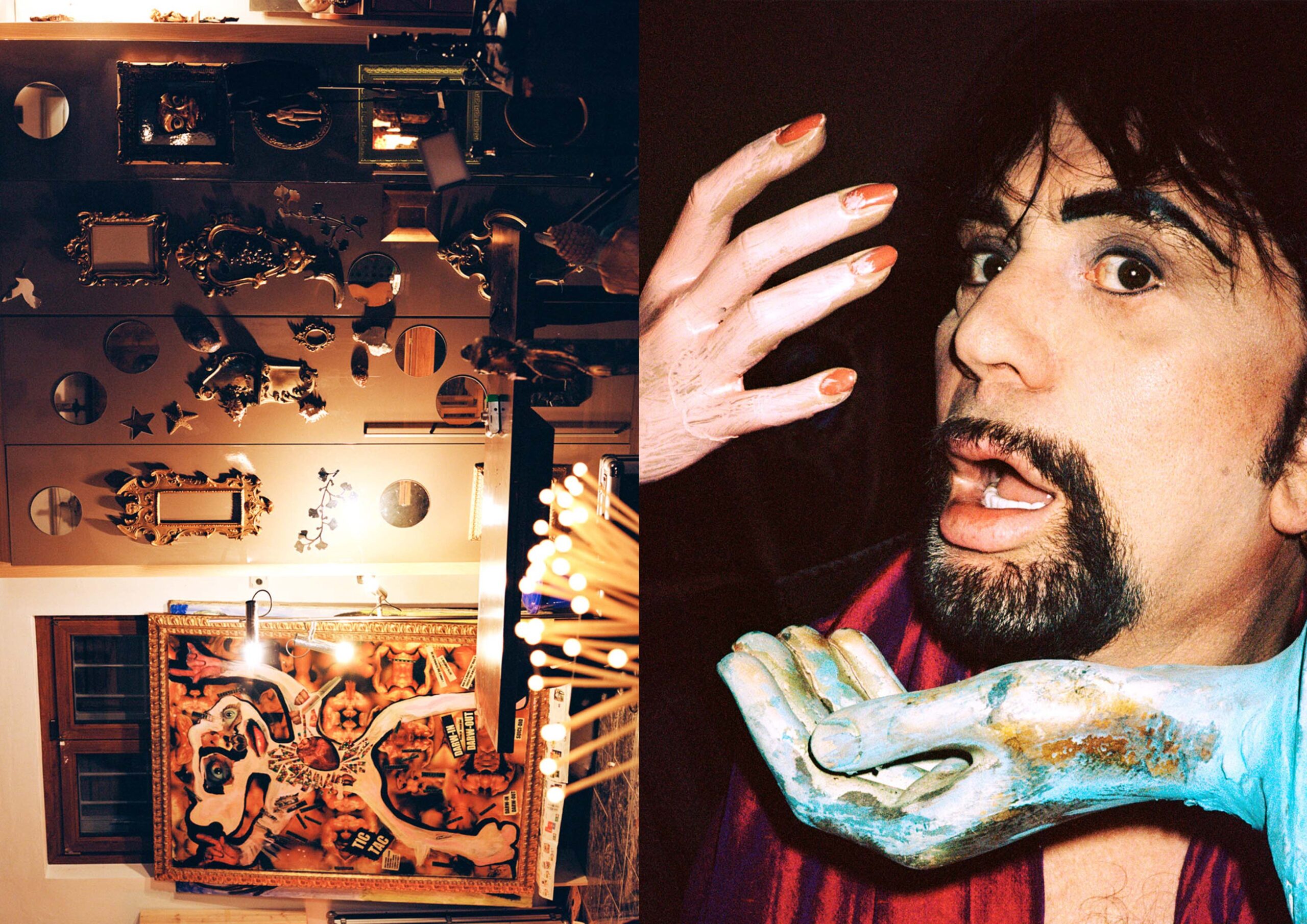

Aperitivo with artist Ivan Cattaneo At his house and studio

Conversation with Giulia Cavaliere Photography by Leonardo Scotti

-

In 1975, the headliners playing the penultimate edition of the Festival del Proletariato Giovanile [Festival of the Youth Proletariat, a music festival organised by Re Nudo magazine, Ed.] held in Parco Lambro, included Area, Stormy Six, Claudio Rocchi, Lucio Dalla, Francesco De Gregori, Eugenio Finardi, Franco Battiato, Antonello Venditti, Giorgio Gaber, and many more. Among them was Ivan Cattaneo. Cattaneo was a pioneer on the Italian Revolutionary Homosexual Front and the first musician in the country to come out, for which he would pay the terrible consequences of the mindset of the time. Intelligent, sublime, carnal, and avantgarde in both life and art, Ivan Cattaneo was part of a polymorphous scene: Italian left-wing counterculture, in which his position as a homosexual artist was not fully understood and—importantly—not fully accepted. Before becoming the king of 1960s Italian revival in the Eighties with the albums Duemila60 Italian Graffiati and Bandiera Gialla, Ivan Cattaneo was part of the Re Nudo world. Not only was Re Nudo involved in the Parco Lambro festival but also in theatre and Milanese culture at a time when being gay implied having to fight for your freedom even against those already fighting for freedom. Today, Ivan Cattaneo is a musician and painter. He makes art for himself and is a young man in his 70s. We went to meet him at his home, in the countryside between Pavia and Milan.

-

GCHow are you? What phase of life are you in at the moment?

-

ICI’m good. I’m still in the phase of having run away from success which is, to a certain extent, scary because it implies the mundane. I hate all that for multiple reasons. First and foremost because it distracts from what you have done and what it was. My artistic output, in this case. I only care about amazement.

-

GCAre you often amazed?

-

ICNo, I am very rarely amazed and when I am, it means that the artist is giving me something truly new, for better or worse. The last time I was truly amazed was when I discovered Basquiat, for example, or certain music like Art of Noise. It’s certainly not these rappers amazing me because they’re making ancient music. Rap was born in ’75, Celentano did rap and so did I back in ’82—I had a track called Italian Slip—so it’s nothing new. It’s very hard to amaze nowadays, you have to take away instead of adding and that’s very liberating.

-

GCI get the idea that some people have this as an innate quality while others develop it over time.

-

ICYes, age is a treasure. I just turned 70 and I think age is extremely important because in putting things into perspective, it gives you new perspective. I am convinced that a chemical change happens as we age and this then impacts the intellect. I no longer think the way I did when I was 30 or 20 or 60. I think like a 70-year-old but I do so with all my baggage. I’m not the 70-year-old you’ll find in the bar playing cards.

-

GCNo cards and excellent selection skills.

-

ICExactly. It’s wonderful to be able to say no to certain things. Perhaps, for example, because I have already experienced them and they no longer interest me or attract me. This applies to sex too, there are things that I’ve tried that no longer interest me. If I enter a relationship with someone and it feels like a film I’ve seen a hundred times then I’ll lose interest because I already know all the mechanisms, I know everything, and I get bored. This applies to human beings and the whole world out there.

-

GCYou believed in the whole world out there and you made history by coming out to it: you were the first singer to come out in Italy.

-

ICYes. When I met Umberto Bindi, the first thing he said was, “You’re so lucky, that wasn’t an option in my day.”

-

GCHe was ostracised.

-

ICYes, he was ruined. He was launched by Nanni Ricordi too and Nanni told me all about it.

-

GCBindi was extraordinary.

-

ICHe was incredible but he didn’t have the strength because they were different times and he also had a rather weak type of character: he paid for what he was.

-

GCDid you pay for it publicly?

-

ICNot in the end, no, but I was branded by being gay.

-

GCWhat happened at the Re Nudo festival?

-

ICI did actually pay for it at the Re Nudo Festival because I didn’t know what I was getting into. It wasn’t as underground as I thought. It was one thing when it was us, Valcarenghi, and the others but the situation was totally different at Parco Lambro. I had performed at the Pier Lombardo Theatre the week before to the real Re Nudo crowd, what we would call Radical Chic nowadays. The line-up was me, Area, and Lino Capra Vaccina, and the audience was really engaged.

-

GCWhat happened at Parco Lambro?

-

ICEverything changed at Parco Lambro because Milan’s entire left-wing movement came, there were 200,000 people there. And the people from Lotta Continua and the movement still perceived homosexuality as a petty bourgeois vice. When I started singing and I said, “Darling is a song written by Mario Mieli with my music and it is dedicated to a man because I’m gay”, everything just exploded. They started shouting, they wouldn’t let me play, they kicked me off the stage essentially, screaming the most awful insults. Mario, another guy Jimmy, and I were on stage and the audience behaved terribly.

-

GCYou were part of F.U.O.R.I. as well. [Italian Revolutionary Homosexual Unitary Front, Ed.]

-

ICYes, alongside Mario Mieli, Corrado Levi, and many others.

-

GCThe intense hostility toward the Homosexual Movement and gays in general from a large part of the political movement on the far left is still incomprehensible to this day. It makes you realise just how important your role and your revolution were.

-

ICI don’t think I, or any of us, were aware that we were making history. We copied the feminists in a certain sense, I’m talking about the years between 1973 and 1974 now. We used to meet up like a secret society, often at Corrado Levi’s house, and we’d hold these self-awareness groups: everyone would talk about their lives and their experiences. It was just like Alcoholics Anonymous, people with similar situations meeting up and almost confessing to each other as though what we were doing was a sin or a weakness. It was all secret, all underground. Then I went to Re Nudo and did my first concerts. The first was at Alpe del Vicerè and it was still very underground, not at all mainstream. I remember that I was on in the afternoon and this long- haired guy doing an all-electronic thing was on before me: it was Battiato and nobody even really applauded him but then I went to hear him when I was playing at the Palalido a few months later and he brought the house down. Everyone was whistling and shouting. Certain worlds were very separate, protected in some way. Then you would leave those worlds and come up against the Stalinist or Catholic left which was very closed-minded and very dogmatic. They judged us gays for being sick or people who had chosen to be depraved. It was something they couldn’t accept.

-

GCWhat was your relationship with Mario Mieli like?

-

ICI was his friend, and he didn’t have many friends because he was quite hard work, to be honest. He had a very strange, pseudo-intellectual attitude. As well as a beautiful brain of course. But it must be said that the early Mario Mieli was nicer and more friendly and then drugs and acid got in the way and he lost his sense of reality a little. He was an extraordinary man though. Of all his books, I loved Il Risveglio dei Faraoni the most because he let himself go in that one and it’s amazing. We used to go to his house and experiment. We got high on ether. We were very, very young but it was great. You couldn’t really form a group with him because he was a leader. He was leader material and you were at his mercy. I often ask myself what he would be like today if he were still here.

-

GCDo you have an answer?

-

ICI don’t know. He was already an Aldo Busi type times a thousand back then, now he’d be an incredible character. He’d probably be right-wing, having gone all the way around via esoterism and alchemy. A D’Annunzio-style far-right character but always a revolutionary, I don’t think that he would like today’s left, just as I don’t.

-

GCWhat has changed in terms of political momentum on the left since the Re Nudo times?

-

ICOur left was about creativity and civil rights but it was less organised. There are very precise civil rights matters nowadays. Our intention was to change the world, to change ourselves. Thanks to that period of our lives, we all changed our attitude towards life to some extent. Politics is less important today, it’s more technical and so it’s different to what it was for us. We didn’t really bother with the politics that happened in parliament.

-

GCWhat do you think about coming out today, especially by public figures?

-

ICLots of people simply never came out and would be ridiculous if they did so today. Coming out has an existential purpose and I think it’s always lovely when someone does it. But it most often happens in the world of entertainment when there’s something to sell.

-

GCYou wrote Polisex which is an eternal polyvocal manifesto for fluidity.

-

ICWhen I wrote Polisex 43 years ago, I did so with the intention of discussing fluid sexuality. Then came LGBT and all the rest but that’s what the song was about. It was all quite naïve but I was the only one talking about this thing and I called it Polisex.

-

GCDo you remember writing it?

-

ICOf course. One evening at Villa Litta, after a concert of mine back in ’78, a person came into the dressing room and I couldn’t tell what they were. I asked, “Are you a man or a woman?” and they said, astonished, “You of all people are asking me that question?”, then they added, “I’m polisex.” I really liked the word so I wrote a song about it.

-

GCThere’s that incredible line that goes: “leave the heart out of this”. It really struck me the first time I heard it. It was such an explicit invitation to set love aside for the minute, among all those other Italian love songs.

-

ICI wanted it to be clear to everybody that I was talking about sex because there’s a whole world of difference when it comes to sex but there’s only one true love. Do you see? So I said “leave it out” because it’s something else and I was talking about sexuality. When I’m talking about love, there is no nuance. Love is love and that’s it.

-

GCYou worked as a stylist before that word became fashionable. You helped to conceive and create the character of Anna Oxa for her 1978 album Oxanna, which was incredibly avant-garde for the time.

-

ICYes, Ennio Melis, who was director of the RCA and a great man, called and said: “I’ve had this singer for two years, she’s got an amazing voice but she ain’t nothing to look at!” She was a very young and ‘normal’ girl. I had just got back to Italy after being in London with Roberto Colombo, rehearsing at Abbey Road Studios and all that. It was ’77 and punk was just emerging so there was this new vitality. Safety pinks were back and inverted swastikas and naturally nobody got it, they thought I was a fascist. To the point that I was once with a friend who dressed the same way at a Dario Fo play at the Palazzina Liberty and we almost got beaten up. I styled Anna Oxa in the punk vein but I wanted it to be Italian punk because the song she was taking to Sanremo, which was her first public appearance with the new look, was anything but punk!

-

GCComing back to your music career, you left the music industry at the height of success after the release of your revival 60s albums because you felt trapped. And you found great relief and fulfilment in painting.

-

ICYes, if I don’t paint in the evening before going to sleep, I think about the things I’ve done and if I haven’t achieved anything that day I can’t sleep. But if I’ve painted or written a song I like, that gives me satisfaction. I truly believe that the artist does things for themselves, not for others. The designer makes a chair for others, but the artist has to do things for themselves and do things that they like. If other people like them then all the better. But the artist who does things to appeal to other people is a kiss-ass and therefore not an artist.

-

GCHave you ever wanted to do things to please others?

-

ICNo, never. I have to say that I’ve never done it and I wouldn’t be capable of it.

-

GCI’d like to ask you a very personal question, by which I mean I’m asking it for personal reasons: I know that you met David Bowie, would you tell me about it?

-

ICI went to London after leaving school in ’71. I met him through Mark Edwards. I remember giving him a scarf at Portobello but he left it behind. I think he was a bit of an arse. On another occasion, he invited us to his house for dinner but then he opened the door and said he had changed his mind. I got the impression he didn’t like me.

-

GCWhat about painters? Did you meet anyone you’ll never forget?

-

ICFrancis Bacon. He lived in my neighbourhood. He wasn’t very clean and he had a drinking problem but he was very friendly. I used to bump into him at a local bar and he was very down to earth.