Breakfast with scenographer Margherita Palli

at her home in Milano

Conversation with Carlotta Tonon Rubini Photography Marta Marinotti

-

Margherita is the most famous and in-demand set designer in the world, yet her trademark pragmatism and lively mind mean it doesn’t occur to her to flaunt it. She signs her name Palli Rota, having been with architect Italo since ’76 and when it comes to work, they “help each other, when needed”. They have a lot of fun together. Italo is responsible for the collections in the house, Margherita for the cats and the odd twist: that’s her strong suit, along with set design or that visceral relationship with opera that leaves you breathless. Or the relationships she fondly remembers with her students, past and present, lucky them. We talk of this and more.

-

CTI am so happy to meet you and I would like to retrace your journey from the beginning, although I do nurture some doubts over what a beginning really is. You studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, which I have always found magical, courageous and rash.

-

We smile.

-

MPIt wasn’t easy to go there back then.

-

CTA lot happened in Milan in those years and you were from Ticino, a ‘foreigner’.

-

MPVery proud to be from Ticino.

-

[Laughs]

-

CTSo what happened?

-

MPI would come to Milan with my parents, I knew the city. I had to retake a few years of secondary school in Brera because there was no equivalency back then. Then I enrolled in the Academy of Set Design. It wasn’t a choice, it was the option that seemed least strange to my family, in that it was still a profession, not something vague. It was structured across four years and one of the professors was Tito Varisco, who was the director of the technical office at Teatro alla Scala as well. However, it felt very old-fashioned for my taste, so I kept my eyes open... I was the diligent type though, so I did my homework and went to Alik Cavaliere’s sculpture class. After a year, I began assisting him: I had decided to become a sculptor. Later, on his advice, I started trying other things. At a certain point, I ended up in the Triennale alongside Pierluigi Nicolin – Italo worked at Lotus with him – and Gae Aulenti... She was involved with both the museum and the magazine, she knew I had studied set design and her assistant was absent. So, she asked me to help her with “a thing” at the Scala, where she was preparing Donnerstag aus Licht with Luca Ronconi. I recklessly agreed. I’ve only worked as the “assistant” a few times, three to be precise, then I started working alone.

-

CTOnly three times?

-

MPIt was by chance. I worked on a show at the Scala with Ronconi, then another with Ronconi and Gae Aulenti, again at the Scala, then with Gae in Pesaro where she was also directing. After that one, Ronconi noticed me for some reason.

-

CTA set designer works when called, there is no regularity to your work.

-

MPAfter this recent period, the show I worked on in Austria is starting up again. It’s a little opera written by a very young composer, I created it with a German director friend who lives in France. Next year I’ll be at the Scala for Rigoletto e Fedora. Otello came about during lockdown. Then there are the exhibitions.

-

CTSpeaking of which, on the one hand you do set design for theatre, and on the other?

-

MPWorking on exhibitions is part of my repertoire. I’ve done them with Nicolin, with Ronconi, a few things with Italo too. Now I’m working with Francesco Stocchi on an exhibition on the island of Porquerolles for the Foundation Carmignac.

-

CTAnd you teach a lot.

-

MPYes, that keeps me busy. I got into that almost by chance, but I do have teaching in the family. My grandfather had a passion for teaching, he co-founded the Circolo Operaio Educativo. I would never have thought to teach. Then, one year, Franco Quadri recommended me as a substitute teacher to Gianni Colombi. Professor Varisco, who had taught me, was nearing retirement. I really enjoy it. All my assistants are former students. And many teach set design at NABA. But almost all of them are former students who first gained experience in the job and then came back to teach.

-

CTDo you need qualifications to be a set designer?

-

MPThe only time I was ever asked for my diploma was when I started teaching because, obviously, you can’t teach at a certified state school without a degree. I try to teach every aspect of theatre, which is composed of many different professions: there are students with less creativity but a gift for working that emerges, for example, in the workshops. Or those with a talent for production or design. You need schooling in theatre nowadays, perhaps even more than before, because there are so many different technologies and you can’t learn these systems anywhere else.

I try to teach every aspect of theatre, which is composed of many different professions: there are students with less creativity but a gift for working that emerges, for example, in the workshops.

-

CTDo the different theatres interact? How does that happen?

-

MPThere is an amazing film from 1991 by István Szabó, called Meeting Venus and it’s all about what theatre is. Theatre isn’t a static study, you know, especially opera. You go to Vienna and you bump into a costume designer you met in Tokyo, then there’s the stage technician that moved from Vienna to Berlin... You get to know each other of course, you meet these people again and again. Producing a theatre show means being inside something. You occupy that space for 20 days, from morning to evening, in a place without windows, with the same people. I think that theatre itself is a place, if you like...

-

CTIs it a democratic space?

-

MPYes. It really is a place where nobody cares about where you come from, which language you speak, or which religion you practice. Part of the nature of theatre is that you have to live alongside everybody. It’s like with languages. In the theatre, we speak a kind of Esperanto. I’ve actually recently written a theatrical dictionary with NABA (Margherita Palli, Dizionario teatrale, Quodlibet, Milano 2021). The language of theatre is mixed. I worked on Chovanščina at the Scala with Mario Martone. Gergiev speaks very good English but he’s from Russia. The orders on the scores are in Italian because the score is written in Italian. Anything to do with ballet is in French. We always had interpreters at those rehearsals, two of the singers only spoke Russian. So, they spoke to Gergiev in Russian, and he would reply to Martone in English but the complex concepts were in Italian and the interpreter Anna had to maintain the rhythm. Gergiev understood her and would add in even more.

-

CTThis is very interesting from a cultural and social perspective as well.

-

MPEveryone speaks perfect Italian in the theatre but from the libretto for Verdi’s opera. So there’s this strange language, these relationships between people who might not see each other for five years and then they pop up again out of nowhere. Bear in mind that it’s also an environment that is always dark. Once you go inside, you can’t tell whether it’s summer or winter outside.

-

CTYou talk about opera a lot.

-

MPI’m the only one in my family who can’t sing. They all played music and they would take me to the opera when I was a child. I like the theatre as well.

-

CTDo you go to contemporary music concerts?

-

MPOh yes, I just really like music.

-

CTAnd what about ballet?

-

MPI used to hate ballet, it wasn’t something that interested me, I had only seen a few things by Nureyev. But then a while ago, the Scala called me for the Balanchine ballet from New York, which is a strange operation because the Balanchine Trust foundation is behind it. Who knows how much of the original Balanchine has remained? Italo gave me a book and some of the photos have nothing to do with anything. The choreography is identical, it’s Balanchine’s choreography. So, given that we had to follow Balanchine’s steps, we reconstructed every movement and I discovered that ballet can be interesting. There is extensive geometry involved, which I had never considered. And then I like all modern dance.

-

CTAnd how much are you influenced by installations and architecture?

-

MPI always begin from the assumption that even an exhibition embodies a certain narrative, that it has something to say. I also worked on the birthday for Striscia la Notizia, which was something else...!

-

[Laughs]

-

MPI’m not a parvenu to culture. The subject has to be interesting and so does the person I am working with.

-

CTDo you work with Italo?

-

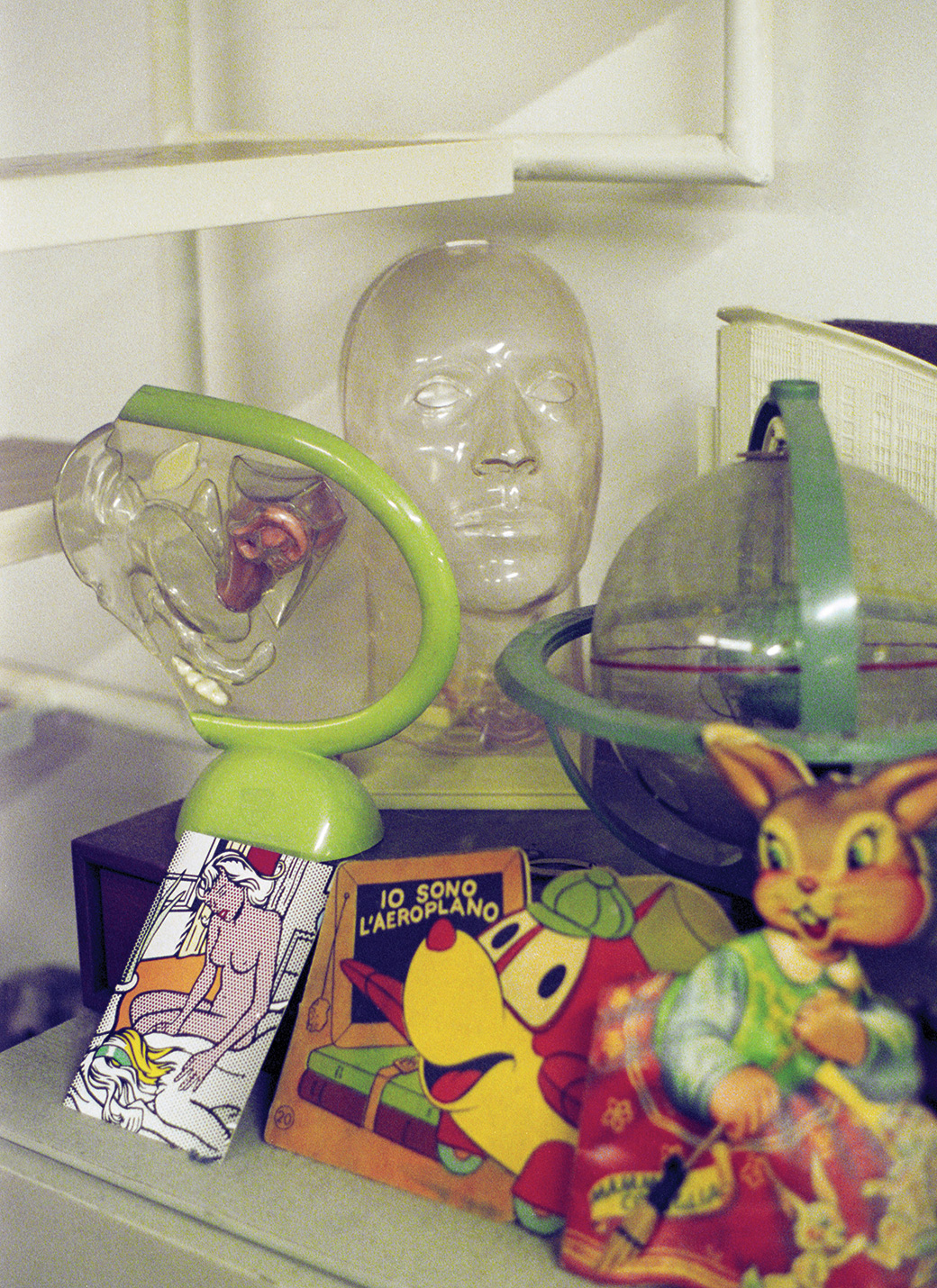

MPHe comes as a spectator and I go to see his work. We help each other if needed, but in no official form. We work together in everyday life. For example, we’ve never owned a home, I never wanted to, but then we found this house, the former Massimo De Carlo gallery and now we have a fixed point for our continuous collecting.

Producing a theatre show means being inside something. You occupy that space for 20 days, from morning to evening, in a place without windows, with the same people. I think that theatre itself is a place, if you like…

-

CTAside from your friendships, do you women in the arts, in set design and design, feel that you are part of an avant-garde?

-

MPI’ve never really thought about it. I didn’t grow up in an environment where this was an issue. At work, of course, I still don’t have many female colleagues.

-

CTAnd are you respected?

-

MPOf course. You’ve got to know how to earn respect too.

-

CTI read that you have loaned out your archive.

-

MPI started working on a computer. I believe I was one of the first set designers in Italy to make this transition and when Ronconi went to the Piccolo Teatro, I loaned out my paper archive so that young people could use it. It’s much easier to archive now. I’m quite nerdy, I love technology. I couldn’t have written the book 20 years ago without what I know today. We also dedicated a section to superstition in the theatre. They would say otherwise but everyone is superstitious, even the “non-believers”.

-

CTDo you have any superstitious habits that you are happy to share?

-

MPI never watch my shows. I get a few glimpses at the dress rehearsal but I never go back to see them. It’s not that I don’t supervise them, I go to the theatre and check everything, but I don’t watch them in the theatre. It’s something personal. But there are some really sacred rituals. In Germany, you must never come on stage wearing a hat. Only if it’s part of the costume. Then there are the colours, purple brings very bad luck in Italy, for example. They’ll say it’s not true but if you show up wearing purple, somebody will always ask you if it was really necessary. We did extensive research into it all and everything derives from something. In Spain, for example, yellow brings bad luck because the other side of the muleta is yellow and it is the last colour that the bull sees before he dies. There are so many in Russia. When a theatre is built, it can’t be opened until a cat has entered but if a cat enters a changing room or goes onstage during a performance, that’s terrible luck. There’s a lot mixed up in it: ritual, religion, superstition.

-

CTYes, they are all mixed together.

-

MPPlease call me by my first name by the way.

-

CTThank you, Margherita.

-

MPSomething else typical of the theatre is that we all address each other informally. There is one stage technician slightly younger than I am who keeps calling me ‘Ma’am’. And I keep telling him that I know he wants to be courteous, but theatre is very... informal. We work together.

I’m quite nerdy, I love technology. I couldn’t have written the book 20 years ago without what I know today. We also dedicated a section to superstition in the theatre. They would say otherwise but everyone is superstitious, even the “non-believers”.

-

CTDoes your work come to an end after opening night or at the end of the tour?

-

MPWell, it all starts with us working all together. There can be all sorts of reasons for which changes are made during rehearsals. Then there’s the dress rehearsal followed by opening night. Perhaps during opening night, you find out that there are other things you can change. Obviously you can’t start from scratch. And then there’s the tour during which you have to fix and modify things very quickly.

-

CTWhat are the directors like?

-

MPI remember Carlo Maria Badini, a gentlemen, back in the Eighties. We would address him formally. He was always in the theatre and he kept his eye on everything. He came to rehearsals too. There are directors who only come when an important conductor is present or to share pleasantries in the foyer on opening night. That makes a difference. Another example is Andrée (Ruth Shammah, director at the Teatro Franco Parenti in Milan), who is always there. She started out in theatre, she has done everything in theatre.

-

CTSome people say that opera is a niche phenomenon, would you agree?

-

MPIt’s niche only because it’s expensive. The communication has an impact too, nobody tells you that Patti Smith is in the audience when Verdi is on at the Scala. I came from a privileged background. All my classmates came from families who went to the theatre or worked in the theatre or had a very young fanatic in the family. I see all sorts of people now, there’s a mix. And there’s a varied public in the theatre too. Italians don’t go to the theatre as much as others, even though we have the most amazing shows. Andrée is always amazing, I would imagine that many people have discovered theatre because of going to the Bagni Misteriosi. It also depends on who’s doing it because otherwise people won’t come back, especially young people. I hope that they are interested in performative theatre. I think young people attend opera and prose theatre with great passion, and sacrifice too.

-

CTYes, also because watching on video...

-

MPIt’s not the same.