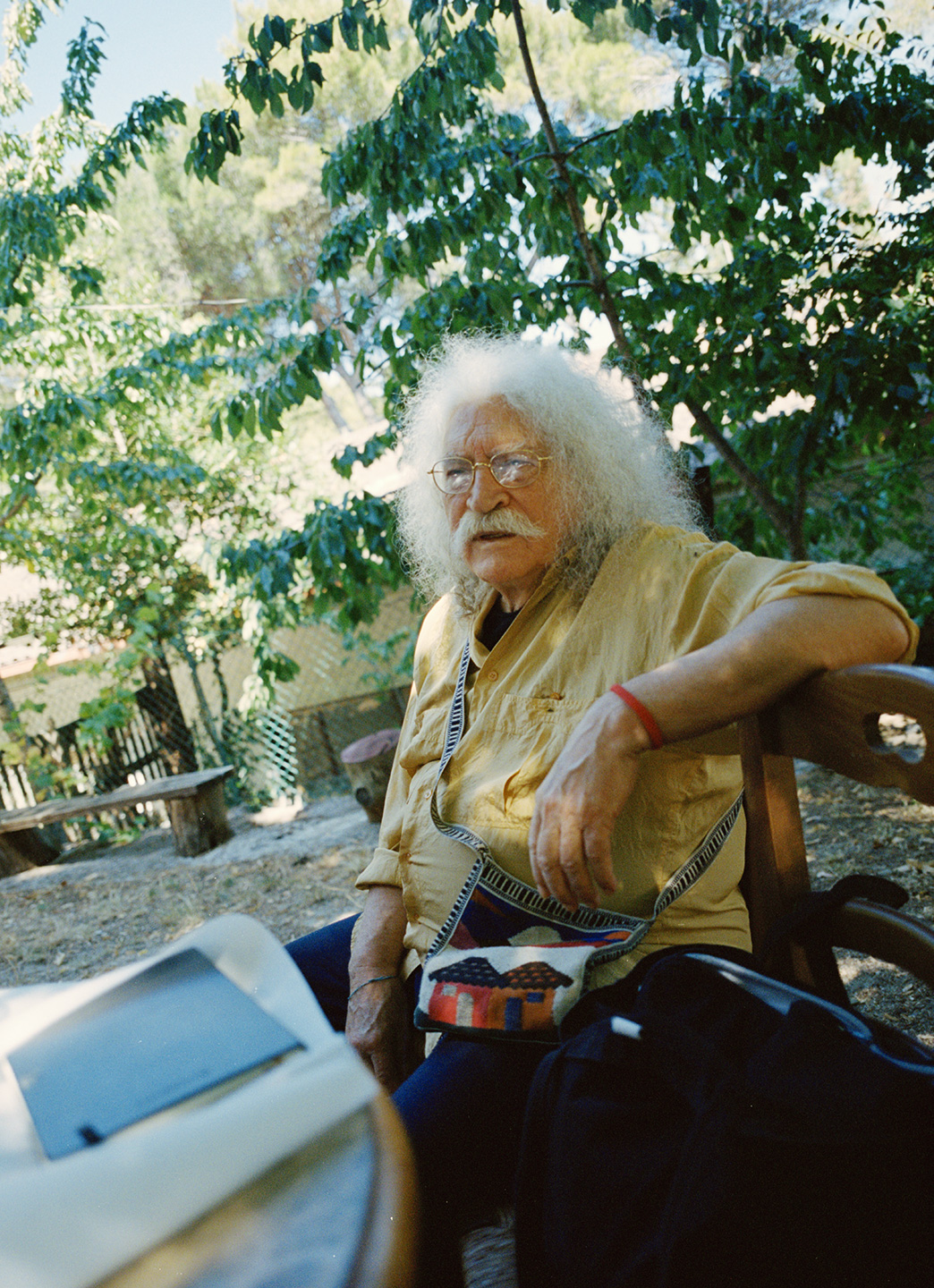

Lunch with editor of legendary magazine Frigidaire Vincenzo Sparagna

at Frigolandia in Giano dell’Umbria

Conversation with Davide Giannella Photography Domenico Nicoletti

-

Contemporary art, reports on heroin from Thailand, original comic strips, and experimental cinema, avantgarde music, farce, situationist content and biting sarcasm all coexisted peacefully and free of hierarchy on its pages. It is still today a point of reference for anybody considering a new contemporary culture project in the publishing industry. Not just a magazine but a hub (as we would say nowadays) of ingenious minds that didn’t all think the same way but were united by their constant quest for beauty. This forty-year adventure is described to us in detail by Vincenzo Sparagna, long-time director and founder (along with the Cannibale group: Tanino Liberatore, Massimo Mattioli, Andrea Pazienza and Stefano Tamburini) of the magazine. We chatted to him, on his birthday, in the Imaginary Republic of Frigolandia: home, cultural centre and Frigidaire archive in the heart of Umbria.

-

DGVincenzo, we’ve been immersed in the archives for almost 48 hours now (any hours not in the archives were spent around a table with plenty of guests), digging up incredible things and fantastical stories from every nook and cranny. Perhaps we should try and get everything we have seen, read and commented on so far in order...

-

VSWhen the Cannibale stuff all started, followed by Il Male and Frigidaire, it was ’77 so I was already 31 years old. I had priors, of course, to use criminal jargon. My background can be split into two areas of interest. One was artistic: drawing, theatre and more over the years of my youth, which can in some way be traced back to the influence of my father, Cristoforo Sparagna, who as well as being a man who suffered a lot and worked very hard, was also an extraordinary painter who didn’t pass his stylistic perspective on to me but gave me my passion for images. The other very important part of my life was my role as a militant and a revolutionary, which I still identify with today. Somebody not so much committed to an objective as to a process of change within society. A process that aims to create a society that is both more equal and more beautiful, since I am utterly convinced that a more equal society couldn’t possibly be uglier because then it wouldn’t be equal. So I think that the search for beauty – not necessarily understood in its Apollonian or Venusian forms – in all its visual intelligence and its essence as something profound that resides within the human body, can vary widely in form, just as it has over the course of the centuries. Anyway, I was a revolutionary militant. This took me on various adventures within the movement and on many trips to South America. Having my own personal position with respect to Marxist critique, in ’72, I found myself disbarred for petit-bourgeois subjectivism from the Avanguardia Operaia, which I had helped found but was becoming, in short, pro-Chinese. I wrote for il manifesto at the time too, free of charge, of course, because the defining characteristic of my life – I love saying this and it’s not for show – is to get lots of money so that I can work for free. Then at a certain point, Il Male was born, with the movement of ’77. It was a very important time. I participated extensively up until the Bologna convention, with opinions that differed from the Autonomia but were very left of where the Communist Party was at the time. So, those were my priors. That was my background when I arrived on the Il Male editorial staff, in time to work on the third issue. I wrote this first editorial ‘O tempora o Moro’, which forecast that Moro was going to come to a bad end, and then he was kidnapped a week later. The magazine got taken to court and I with it. One of my many court cases. Il Male immediately took a stance outside of the entrenched terrorism versus state lines. Not neutral, because being so much further left than the presumed terrorists and, needless to say, the state, we could afford to mess with the Brigate Rosse – who we knew anyway – just as we could make fun of Cossiga with the same distance and clarity. So Il Male was also a political means of saving the creative momentum of ’77 in a way, freeing ourselves from ancient and avantgarde ideas alike. Because the twentieth century was the victim of its own kinetics, always moving forward in this illusion of progress and linear time only to realise that gradually, instead of enriching, it was merely consuming, rendering the entire universe of human knowledge unexplored and lost. The movement of ’77 was related to the discovery of the post-modern and this involved comics, satire, drawing, and the whole world of images and graphics too. You could easily merge a Greek structure, the Parthenon, with Mondrian or Andy Warhol, or use Michelangelo and make an excellent adventure comic like RanXerox or reinterpret German expressionism like Scozzari did. Or make fantastic drawings like mine or be a designer like Andrea Pazienza, who ranged from the most perfect light-hearted classicism to Walt Disney. All these generations came together at Il Male. Frigidaire was a project that combined all this with something that I thought was essential at that time, and still do actually: this ability to get inside the story in the simplest yet equally the most elaborate way possible. It’s a matter of writing style, of reportage and narrative, because essentially the story of the contemporary world is a story of words and images, from photography to cinema and all the rest. But it is also a matter of words that provide structure, meaning and occasionally contradiction; sometimes they distract you and prevent you from grasping what you are seeing. In this sense, Frigidaire was a comprehensive communication project. The meaning of this research developed and enjoyed a kind of new renaissance with Frigolandia. And this is the really interesting part: a mechanism was created whereby there was this simultaneous dream of this imaginary republic, which, as you know, is the first maritime republic in the mountains. This is both because from our location on the slopes of the Martani mountains, we overlook a large plain which, at night, lit up by the occasional lamp, looks like one of those dark bays where fishing lure lights sail in search of fish, and because in the end, the sea – especially for me since I was born in Naples, although I then moved to Rome but you know, you carry it in your heart – is like Brecht’s black woods, of which he said “I was born in the black forests and part of those black woods will always be in me”. So I carry all this sea inside me, there’s nothing I can do about it...

-

DGThat feels like the right cue to talk about what you imagined for Frigolandia and, therefore, Frigidaire and all the energy it generates.

The twentieth century was the victim of its own kinetics, always moving forward in this illusion of progress and linear time only to realise that gradually, instead of enriching, it was merely consuming, rendering the entire universe of human knowledge unexplored and lost.

-

VSNaturally there’s a paradox in the fantastic construction of Frigolandia, which lasted 15 years and was marked with important events, exhibitions, initiatives, newspapers, books and so on. Frigolandia has definitively matured in the past 2-3 years, in part helped by the fact that Yale University purchased part of the archive, which gave us enough money to pay off our debts and live easy. Unfortunately, the Municipality of Giano dell’Umbria – an establishment with no vision run by ambiguous figures and politicians that lack any insight in terms of decision-making – chose that moment to send us yet another notice. They had been sending us letters, each more ridiculous than the last, for some years, which we always replied to, but when a new mayor from the Lega party was elected, they decided to send an eviction order in the middle of lockdown. The order is an administrative act that invokes a legal quibble about beach concessions, but I won’t bore you with the details...

-

DGThe sea crops up again...

-

VSAnyway, we’ve had to turn to the Regional Administrative Court so we’re asking for as much support as possible so that we can deploy that solidarity in all its forms – videos, texts, articles, etc. – when we ask for a hearing. In the meantime, we’ve filed an appeal and this tribunal will have to decide whether to shut our business down, despite the fact that it’s going well and it involves thousands of people, which would leave the place empty and abandoned, or evict us and leave the place empty and abandoned. One of the two. It’s bizarre but we can’t exclude the most absurd outcome. I think the Ministry for Cultural Heritage should intervene because this is cultural heritage. You know us and the place, so you know that there is an incredible archive here, thousands and thousands of things, photographs, drawings, this and that. Emptying this out for nothing and risking the loss of much of these works is madness no matter which way you look at it. Totally incomprehensible.

-

DGWell, Vincenzo now that we’ve got this broad overview, I’d like to ask you about a few specific events.

-

VSOkay but someone needs to go and turn off the ragù or we won’t be eating later. It’s the fourth button from the right.

-

DGI’d like to talk about some of your work that evolved into something highly contemporary because it was all about the idea of truth and we live in a time when it is very easy to cite post-truth, fake news and so on. Exploration of this particular tension between real truth and imagined truth or perceived truth, especially in the media, is nothing new, of course.

-

VSIn short, there was a point with Il Male where we just dove headfirst into this territory of the false, which had been touched on by the French situationists or in the odd extemporaneous newspaper experiment in ’77. Very lightly touched on, though, like a distant parody. We just dove right in and didn’t hesitate to get our hands dirty, playing on this element of the statute of truth for newspapers where interfering with this statute of truth became another system of truth and what’s more, with this latter system, you could tell the truth in false form.

-

DGHoax and counter hoax.

-

VSLots of people believed us. I remember coming out of the airport – I was in Paris that week – and catching a taxi to rush to the office and see what was happening. The taxi driver was convinced that Ugo Tognazzi was the leader of the Brigate Rosse because the Brigate Rosse had planned to attack Piazza Nicosia and the news that Tognazzi had been arrested broke at the same time. It was reality grafted onto fantasy. Anyway, there were a lot of fakes. Some of them went to Eastern Europe or Afghanistan. Pravda was a good one...

In short, there was a point with Il Male where we just dove headfirst into this territory of the false, which had been touched on by the French situationists or in the odd extemporaneous newspaper experiment in ’77.

-

DGHow did you get away with that one? I imagine that it was no easy matter operating under a regime that was so attentive to communication. Didn’t you print in Cyrillic so that the readers would understand it?

-

VSOf course, always. It had to be in Russian or Polish, then we made an Italian version and distributed it with Il Male or Frigidaire. We had to smuggle the copies any way we could. I’ve actually still got one last false-bottomed briefcase stuffed with copies.

-

DGWow, real secret agent style!

-

VSFor worst-case scenarios, in case they seized everything, there were more copies crammed into the roof of a Volkswagen. I can’t remember which model, but the roof was stuffed with copies. Because they could search everything at the border, the Iron Curtain. Once they took the side of the car apart to see if we had anything hidden under the seats.

-

DGAnother legend that many of us grew up with is the story of RanXerox and the battle over his name. I don’t know if that one ended up in court too...

-

VSNo, it didn’t go to court. They sent us a cease and desist letter. Tamburini’s character was called Rank Xerox because it was created on a Rank Xerox photocopier, so he named it after the photocopier. When the letter arrived, we were working on Frigidaire, so we had to make a decision. Do we keep calling him Rank Xerox at the risk of a lawsuit? We decided just to call him RanXerox. There was no lawsuit, and the character kept his personality. I think it’s the greatest novel of the contemporary era, this robot that becomes progressively more and more human, condemned to love Lubna for all eternity and therefore to cultivate the most human of feelings, the one that somehow causes you to lose all reason. On the one hand, there is this profound transformation but on the other is this cynical, ruthless, terrible humanity. And then the story came to an end with Tamburini’s death.

Frigidaire is still a magazine that is open to wonder. We must be capable of awe, and not just think we’ve seen it all before. What do we know? We don’t know anything, everything is still to be discovered.

-

DGHow do you see the contemporary evolution of the comic? You continue to invest in the medium, or rather the language, of comics and to feature them in your magazines, why is that?

-

VSThe comic has stabilised, from a certain point of view, as a form of storytelling and communication. In that sense, there is no need to rediscover gold in the Klondike, we’ve already discovered it. We do have to keep digging, however, because there are plenty more veins and new ones are constantly emerging, and that’s just in the European and American comic segment, and Japanese to some extent. Comics have seen huge growth and are accepted as an artistic language in all respects. There is no end to invention, thank goodness. Thank God Frigidaire is still a magazine that is open to wonder. We must be capable of awe, and not just think we’ve seen it all before. What do we know? We don’t know anything, everything is still to be discovered.