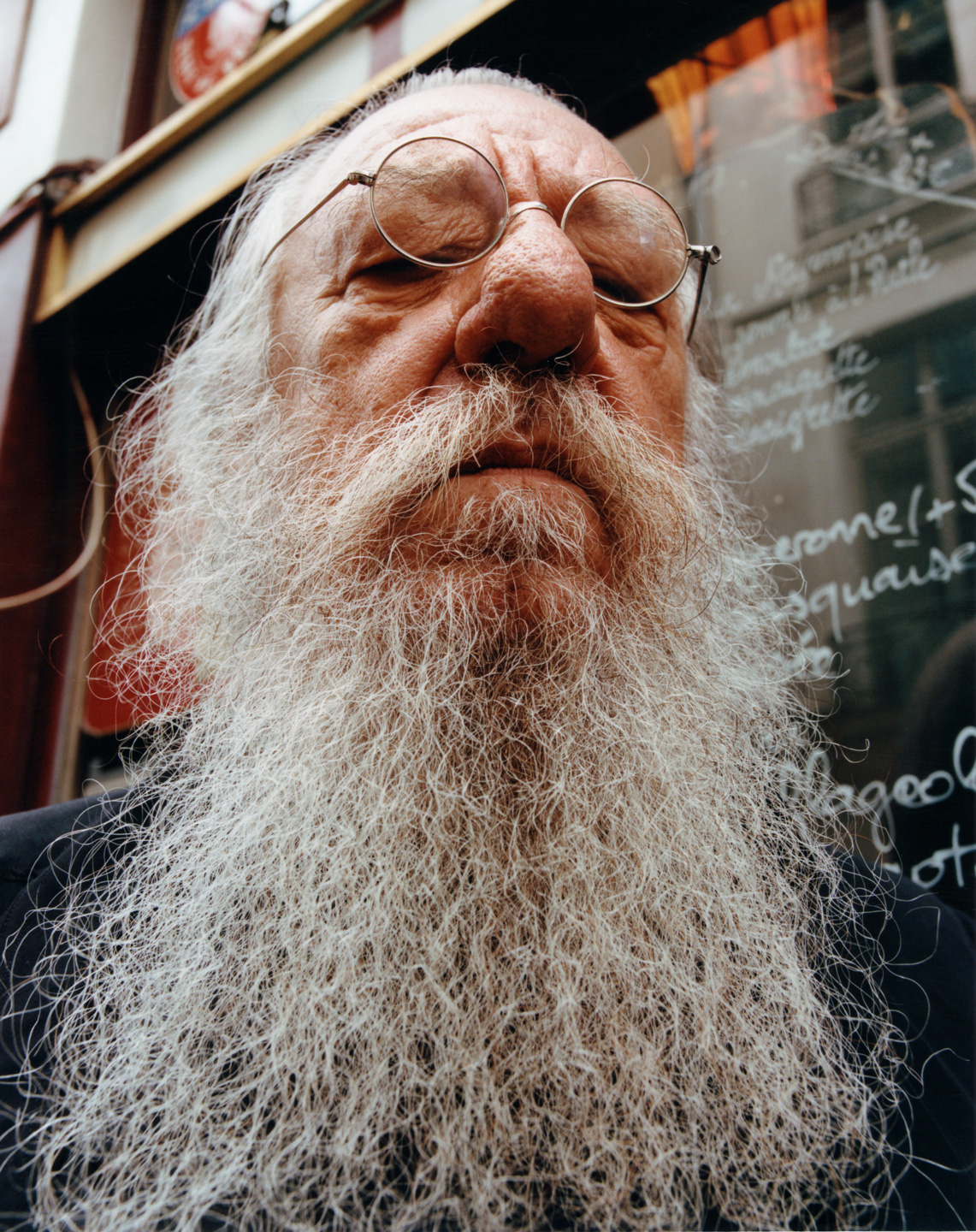

Lunch with iconic photographer Harri Peccinotti

At La Gavroche rue Saint-Marc Paris

Conversation with Sarah Moroz Photography Maciek Pozoga

-

SMHow long have you been a Parisian?

-

HPOh god. Probably more than 50 years. But I’ve lived here quite solidly for the last 35-40 years. I used to live half in London/half in Paris; then we gave up London because it was stupid to have two places – and too expensive. I’m married to a French lady, Genevieve.

-

SMDo you exchange in English or French?

-

HPWe speak together in English. She won't speak French to me. I’m too bad at it.

-

SMWere you drawn to Paris for professional reasons?

-

HPYeah, I was doing graphics and photography in London, but I was working in Paris half the time, in the late ‘50s-early ‘60s.

-

Waiter brings wine, trickles it into glass, and sets down terrine

-

SMCould you tell us about your professional trajectory?

-

HPI was brought up in London, born in SoHo. I left school at 14; I ended up [takes a bite] – bon appetit – in the art department of a big factory. This is 1950, just after the war; their art department did hand-lettering, graphics, layouts. I did a semi-apprenticeship in graphic design. They had a little studio with a Rolleiflex. You had to produce everything by hand, because there was no letter set, no photo setting. It was commercial art – there was no such thing as art directors; there was no special word, you were a training craftsman.

-

SMDid you come from an arty, or even craftsman, background?

-

HPI came from the working class. My father was a plumber, a Communist plumber. He worked for MGM Studios, making special effects: rain and fire and things like that. He wanted me to go and work with him – I didn't get on very well with him, incidentally. I didn't want to do that. I was at school during the war, and I had an art teacher who thought I was good at drawing, and her husband was the chief of this art department in this big factory. So, she said, “Why don't you go see my husband?” And I thought, at least I would escape my father. [laughs] So they employed me; I worked there for two-three years. Then I played music for a couple of years, then I did a lot of record sleeves. When I was a musician, I met up with a drummer called Carlo Kramer who owned Esquire Records in London, and they recorded all the local modern jazz. He knew I was doing graphic design – he was blind, incidentally, which was not helpful for knowing about design. But he had a wife who was astute, and could see perfectly. [laughs] So I didn't get away with anything. Then I went into advertising – design, then art direction and photography – then into magazines. I was mad for graphic design: the De Stijl movement, Bauhaus. I used to go see the places where Mondrian painted. Graphic designers started to move into magazines because advertising was too boring, too much control. Magazines, from 1962 to 1968, were very free – not like now, where advertisers tell you what you should do. It was really a sort of adventurous time. Then I did Nova, which is what everybody wants to know about. And then I went off, freelance, doing graphics and photography, until now, which I still do.

-

SMThat era that everybody wants to know about, was that a key time for you too?

-

HPI suppose it was a key time, that was when things were happening for me, mostly. The ‘60s caused all the trouble in my life, the good and the bad, all at once. It was a good time. I find it a bit stifling now.

-

SMHow so?

-

HPI mean when you do fashion, things like that, the advertisers have more control than the editorial. In fact, they edit, and the editor does what they say. Don’t quote me too much on that. People are like Christmas trees when you photograph them: covered in things, though I try to photograph them as naturally as possible.

I was mad for graphic design: the De Stijl movement, Bauhaus. I used to go see the places where Mondrian painted. Magazines, from 1962 to 1968, were very free – not like now, where advertisers tell you what you should do.

-

SMHas your point of view as a photographer changed over the years?

-

HPI’m pretty much the same. Maybe it’s just old age. Your taste sort of gets stuck. Maybe kids who take photographs now have a different thing in their heads when they start.

-

SMSo, you don't follow what’s going on today much?

-

HPNo. I mean, I keep my eyes open. I’m reasonably au fait with what’s going on in the fashion world because I sort of move in it. But I’m not very good with new technology and things like that. I don't have a website; my son is trying to force me. If you look my name up, all you see is nude girls, which is not – I have photographed some nude girls, obviously – but that’s not what I do. People think I’m some sort of porn photographer. Which is not true at all.

-

SMYes; without a digital presence, you’re at the mercy of the Internet. When I was Googling your name, the Pirelli stuff came up straight away. How would you characterize your work?

-

HPI think photographically I’ve done almost everything: I photographed in Vietnam in ’66, I’ve done books on ethnic communities, I’ve done book jackets, still lives. Anything, and everything. They were commissions, but I’d approach it the same way. If I was photographing this glass of wine, I wouldn't spend four hours in the studio moving lights around to do it. I try to use film all the time but it’s getting very difficult – if you work for a magazine now, they don't like you to use film.

-

SMAnd independently of commissions?

-

HPI photograph a lot of insects.

-

SMDo you go to a lot of photography exhibition?

-

HPI see many more art exhibitions than photography exhibitions. I like photography, but I’m not sure it’s art.

-

SMThat’s controversial! Why do you think that?

-

HPWell not really, but I think the value of photography is a bit suspect. I mean, paintings too. It just depends if you’re dead or not. I was very good friends with Saul Leiter, and just before he died I was in his studio. He had new representation – Howard Greenberg. He said, “Christ, now they’re selling my pictures for money. All this time, I’ve been ignored.” And now, because he’s dead… I think it’s the wheelers and dealers who create the value, not the actual photographs. Suddenly it’s valuable, from an art market point of view. Now there’s an art market based on photography. Some strange pictures are being sold for an enormous amount of money, and you wonder why. The value put on things – financial, not in reality.

-

SMWere you friends with other working photographers?

-

HPArt Kane. Jeanloup Sieff – we had the same agent in about 1960. I used to live almost next door to him; I was on Boulevard Courcelles, he was further down. The 17th arrondissement is pretty dreadful. I live in the 11th now. It used to be all craftsmen when we moved there, but now everywhere is a bar, and weekends are quite desperate. It’s very strange, because now, all the young French girls in my local bar – the 18-22 year olds – they all drink pints of beer now, three or four an evening. I think, God! Equality is one thing, but actually taking on the bad habits is really stupid. You really feel they are forcing themselves, and they all get really drunk. Smoking, drinking, behaving badly – they seem to think that’s equality. It looks like it’s to prove they can do what stupid men can do.

-

SMDo you feel that there are changes in the way women are expected to be depicted in your work?

-

HPI think it has changed.

-

Main course arrives, more wine is poured.

-

HPI used to work at the Nouvel Observateur, and everyone who worked there was drunk. Everyone got drunk and half the writers wrote in bars and drank. And now they drink water and they don't go out to lunch, and it’s a complete different atmosphere.

I think photographically I’ve done almost everything: I photographed in Vietnam in ’66, I’ve done books on ethnic communities, I’ve done book jackets, still lives. Anything, and everything.

-

SMDo you have a routine in Paris when you’re not working on commission?

-

HPI do try, but I’m not very good at it. You have to react to the situation, rather than create the situation. Some photographers are good at creating the situation, I’m not too good at that. I’m a minimalist, so I don't need much. I try to be as natural as I can, but it’s very difficult. Like a good model is someone who can sit down and look like she’s sitting down. Which is quite difficult, because once you point a camera at them, it’s not natural anymore. Others, you can't take a bad picture of – that’s why they’re famous, I suppose.

-

SMDo you need a relationship with a model to get to that point?

-

HPI used to – in the ‘60s in London, models didn't earn any money, it was all very low-key, we all knew one another as photographers and models. Almost everyone had a studio of some sort. You used to have an idea for a model and they’d come; then you’d all go out to dinner afterwards; there was no talk of money. We were all friends. Now it’s like, a model flies in from New York, gets off a plane, comes to the studio, takes a picture, and flies off again. She eats a non-gluten lunch and is gone!

-

SMWere you with your wife during that era?

-

HPIn the early ‘70s; before that I was loose in the street. I was behaving badly like everybody else.

-

SMDo you photograph your wife?

-

HPNot recently; I used to a lot. Now she’s older; she doesn't let me. She was working in photography – she was a stylist, and she was working with an agent I had at the time. She was committed to taking me around and driving me places; that’s how it started. Then she gave it all up and became a Buddhist, and is a translator. She teaches mindfulness. She became very serious.

-

SMI like your vest, by the way.

-

HPIt’s a designer called Hollington; he used to do things for artists. You can’t find him so easily nowadays, it’s got hundreds of pockets. I think César, the sculptor, used to wear it all the time. I wear it virtually all the time.

-

SMDo you need a certain equilibrium between art direction and photography to feel creatively satisfied?

-

HPI probably do more photography, but I also do painting and graphic design. I have this dislike of computers and iPhones; I like paper and pencils and touching things. I find that’s getting lost. On a Mac, it’s never like what you’re doing. The design looks great, then on the screen it looks crap. Before, when you’re sticking things down on bits of paper and scissors, you could see exactly what’s happening. Even if you work on film, it’s digital because they scan in the negatives or prints.

-

SMDo you have exhibitions?

-

HPI’ve got exhibitions happening in theory: one in New York, one in London, and one in Paris for sure. I’m sorting through the pictures, setting it all up. One is a friend's gallery, who is a journalist, who wants to put on an exhibition in his place. London is further away. The New York one will be a book and an exhibition, but I’m waiting to hear. The agent knows more than I do.

-

SMDo you choose a selection, or do galleries want to see a specific portfolio?

-

HPAt the minute I’m choosing. Well, that’s slightly lying. People want iconic – well, I shouldn’t say iconic – but things they think are iconic, which I’m trying to stop. People call up and want bloody pictures from Pirelli.

I have this dislike of computers and iPhones; I like paper and pencils and touching things. I find that’s getting lost. On a Mac, it’s never like what you’re doing. The design looks great, then on the screen it looks crap.

-

SMIf what others view as iconic and what you view as iconic doesn’t match, what would you emphasize instead?

-

HPI would try to use things that were not so well-known, for a start. While looking through all the stuff I’ve done to sort it out, or re-catalogue it, you find pictures that couldn’t be used in 1965 but are absolutely tame and usable now.

-

SMWhat’s an example?

-

HPThere would be a nude you couldn’t use, or a girl for a fashion shoot lost her clothes, or something you’ve made purposefully but was refused. Now you find those pictures, which you’ve kept but haven’t bothered to pay attention to... They had their own quality at the time, but now you can use them. So that’s been quite a surprise. A lot of my work has been commercial. You find – I don’t throw anything away. I lost a lot… a lot got burnt once. Suddenly when you look through an old carrier bag of transparencies, you find pictures that are now very attractive because you’re looking at them with a different eye, and you can remember when some of the things you would’ve liked to have used weren’t used, because they didn’t show the clothes properly. Things used to be wrinkle-free. You find pictures that were refused for the wrong fashion reason, the reason being they looked natural, when they wanted them smooth and clean.

-

SMIs your archive organized?

-

HPNo. I’m organizing it at the moment. And have been for the last twenty years.

-

SMIs it motivating to have the exhibitions?

-

HPI don’t know… but it’s good to start thinking on that level [pours more wine] for a bit, rather than working. It valorises what you’ve already done, which is nice.

-

SMIs it organized chronologically? Thematically? By client?

-

HPIt’s thematic I suppose. The ethnic travel I split into countries because we did books on Cameroon, Nigeria, Malaysia, Micronesia, Australia… we travelled a lot for ten or twelve years. When I came back they thought I was dead.

-

SMHave you ever taught photography in schools or for workshops?

-

HPA little bit, not much. A bit in London and Switzerland at ECAD. I couldn’t get into the Royal College, but I can teach there. [laughs] That’s another thing that’s changed. In the old days, you could get into the Royal College, or any of the arts schools, with talent. Now the more important thing is your educational background: how many A levels you’ve got. And then you become kind of a weekend potter, someone who’s not very good but has the educational numbers. I couldn’t get in now. Hockney wouldn’t have, he had no schooling, so there’s no way. Now they have nothing coming out of there, and they’re very well-educated. But it should be like music, talent is what’s most important; the rest is irrelevant. It doesn’t matter if you can do algebra or not if you can play the violin. You develop by literally doing things. And my friends were all enthusiastic about graphic design. We used to all meet in pubs and argue about whether so-and-so’s typography was better than someone else’s. Now I’m too old to mix with the people who should be enthusiastic, I’m with the ones who sort of remember.

-

SMWhat do you remember?

-

HPAfter the war – I think there was rationing in England until ’55, ten years after the war was over – I think the war was an incredible change. In 1955-60, there was incredible change. In the fashion industry, all models had to be about 25 at the youngest. They were the only ones who got any money. They were all dressed properly. Suddenly in the ‘60s, all the kids were buying army surplus and there was a crazy creative push in England – like the Vivienne Westwood shop – they were inventive, really. I used to collect baseball jackets and cycling things in New York, which were the only things with writing on them; no manufacturer was doing that. Chanel didn’t have two great Cs. Apart from Louis Vuitton, branding didn’t exist. Suddenly everything was saturated. But between 1960-1975, it was freedom. We had the pill [laughs]; people weren’t terrified of getting pregnant, people had a different attitude to their parents completely. Now if you don’t have the right pair of shoes you’re an idiot. And now the advertisers have taken over. Before there was no money – kids didn’t have any money, there was no market for them. There was nothing to sell to them. It was ‘do what you like.’ It would be hard now to break the rules – there aren’t that many rules to break.

Suddenly when you look through an old carrier bag of transparencies, you find pictures that are now very attractive because you’re looking at them with a different eye.