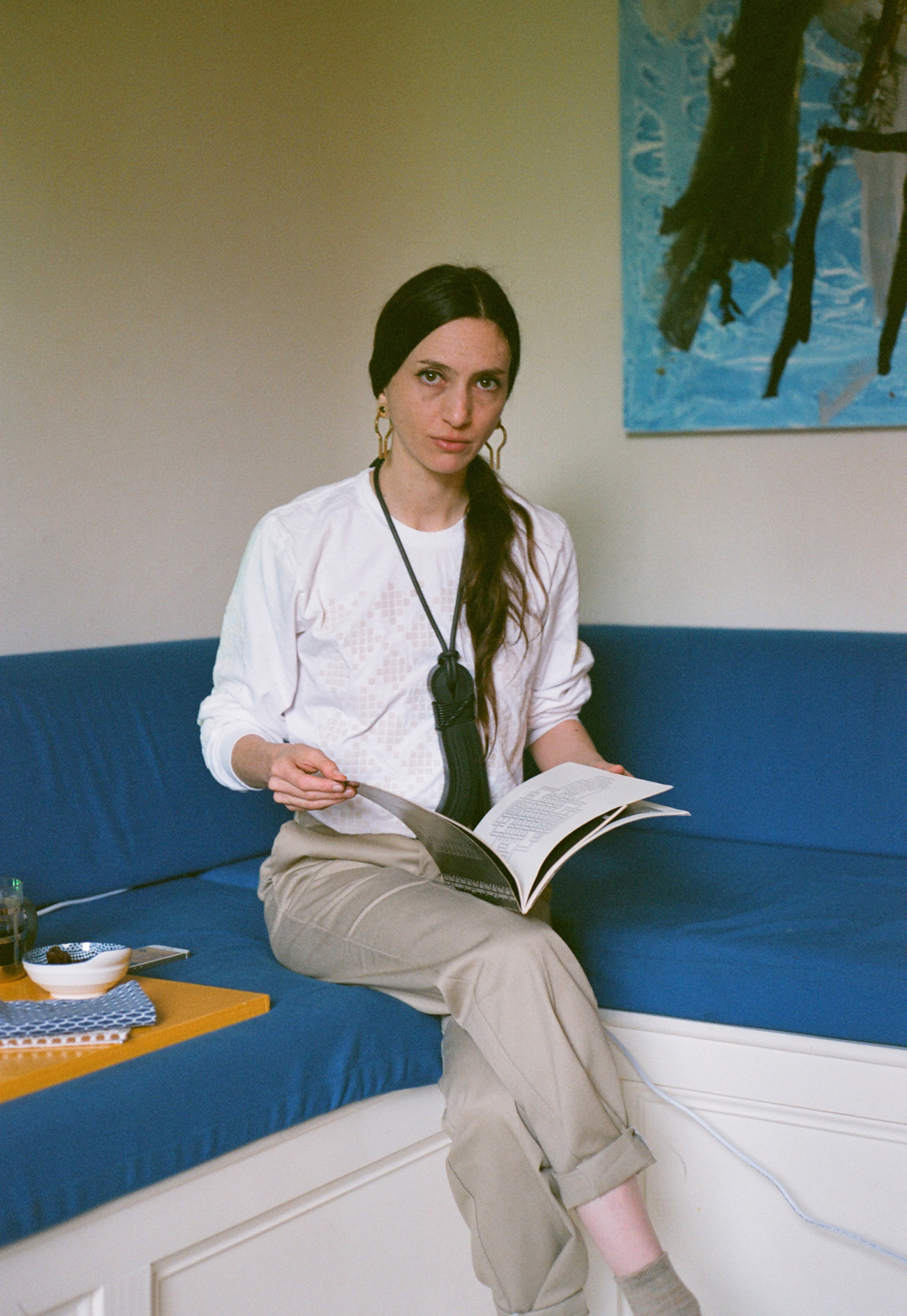

Lunch with Tauba Auerbach

At Tauba’s House in New York

Conversation with Julia Sherman Photography Lele Saveri

-

When the sun set, we decided to go in search of The Aventine Key Hole – a mythical hole in a locked garden gate that frames a clear view of the Vatican far off in the distance. Tauba had been assured that it really did exist; we just didn’t know where it was. We spent hours roaming the city with only this vague objective in mind. When we finally, somehow, found this tiny hole at the end of a pitch black residential street, it was 4am and the only people to be found were parked in cars, steaming up the windows (apparently, this was the Roman version of make-out point). We took turns peeking at the Duomo and then we parted. It was a romantic way to meet an artist whose work I had long admired. Tauba’s work is as alluring as it is smart, drawing on mathematical and architectural theory, linguistics and tetrachromaticism, manifest in handmade glass, woven canvasses, spray paint and instruments. She is right brain and left brain all at once and to the max, and I have to admit I was relieved to find out that despite the incredible volume and range of her creative output, at least she isn’t “a morning person.” As much as I love her coveted objects and canvases, it is Tauba’s side project that really speaks to who she is. All of her critical and market success has inspired Tauba to pour more energy into an endeavour that bucks the commercial art market – her independent publishing project, Diagonal Press. The works she makes under the aegis of Diagonal is smart and thoughtful, personal and meant to be distributed as widely as possible. For every coveted painting Tauba sells through her blue chip gallery, she can sell thousands of enamel pins, ornate rolling papers, books and posters herself at her folding table at the Los Angeles and New York Art Book Fairs. And if you are really lucky, she just might send you a calendar full of her hand-drawn fonts in the mail. This project is a token of appreciation to the people who really get her work, whether they can afford to engage in the craziness of the art market or not. I sat down with Tauba in her Soho apartment, to make a cruelty-free vegan meal, and talk about the optimism of her parallel practice.

-

JSI'm interested in how you think about your life's work as compared to your artwork? What does success look like for you, and how has it changed since you started showing your work?

-

TAThis is such a vast and great question! I can’t imagine trying to answer it all at once though. Maybe an answer will just sort of emerge as we talk?

-

JSThat’s fair; I guess I just jumped in there with the mega existential inquiry right off the bat…

-

TAThat’s totally my style! My friend Sam likes to remind me how I asked him straight out if he was happy – in a really sincere way – the very first time we met.

-

JSOh yeah, if someone tells me they went on a second date, my next question is always, ‘are you in love?’ I am so curious to know how people keep romance alive, in life, and in their work, even as the career part ebbs and flows, which it does for all of us. That’s why I am so interested in artist’s side projects, the “passion projects” that are maybe less visible but so important to the longevity of a practice. In your case, that would be Diagonal Press. Can you tell me what Diagonal Press is exactly?

-

TAThe press publishes books, type specimen posters, paraphernalia, mathematical models, and enamel pins with topological/ornamental symbols. The publications are as inexpensive as possible, mostly made in my studio with office supplies and consumer-level binding machines. I’m trying to push these tools as much as possible, partly to prove that it’s possible to do ambitious things with very limited resources.

-

JSI love that. In some ways, it’s almost an insurance policy against the temptation to make things bigger and more elaborate just because you can. I can think of so many artists whose work got flashier over time, but when I think of their best work, it is usually their most modest early experiments that come to mind.

-

TAI agree. I think it’s a very corporate-minded mistake. I also work with the smallest team possible. I have no ambitions to run an empire.

-

JSSome silly people might find it surprising that you would spend your time, resources and energy on an endeavour that stands in opposition to the very market that has embraced your work. How did Diagonal Press come to be and what role does it play in the way you shape your own career?

-

TAI started Diagonal in 2013 after receiving a crash course in the distinct ugliness that the art world has to offer for a couple of years. It was my childhood dream (other than being an astronaut) to spend all my time making art, and I’m overjoyed that I get to do that. But, when I started having shows, I was as green as a person can be, and I had some painful learning experiences. These days, when artists graduate from school they know how the system works, they’re so professionalized and knowledgeable. I was not. So I was just kind of feeling my way along in the dark, figuring it out as I went, and then suddenly people were going nuts over a certain group of paintings I had made. A few months later my NY gallery announced that it was closing. Then the craziness began.

-

JSHow so?

-

TAI received creepy mail at my house and threatening emails from collectors who couldn’t get paintings. One dealer who wanted to work with me, cut and pasted photos of me and my work into a collage, which I tried to politely ignore, but they just sent it again. In one instance, I asked my dealers not to sell to a guy who had been really rude and disgusting to me while he was drunk one night. To punish me for not making a painting available to him, he bought up a ton of my other work on the secondary market and dumped it at auction. Basically, I just saw a lot of people wielding the power of their wealth in unpleasant and destructive ways.

-

JSWhy was this happening? What caused the frenzy?

-

TAOne reason was that I had kept my prices much lower than they could have been, as some kind of gesture of sincerity. I wanted it to be clear that I was making art for the right reasons, not to get rich. But in that, people saw an opportunity to flip my work for huge profits, so it slowly became evident that my strategy was encouraging the greed I had intended it to stand against. It also created an instance of huge wage disparity – as the artist I had done all the work, but the flippers were making 20 to 100 times as much as I had. Eventually I decided to get over my embarrassment at the fact that people were willing to pay a lot for my paintings, and just use the opportunity to treat my employees well and support causes I believe in.

-

JSWhy is it embarrassing to know that people value your work, and they are willing to pay for it?

-

TAI worried that people were valuing my work for reasons I don’t agree with. Greed is the source of most ills in the world, if you ask me – so it embarrassed me to think that someone might make the wrong assumptions about my intensions. But my thinking has become more nuanced over the time. I went from moving along in a straight line to being more critical, more sceptical and, well, more diagonal. The path of least resistance is hardly ever the right path, in my opinion. So back to your earlier question: the press is an experiment intended as a counterweight to all of this – something that I could build from scratch using all the knowledge and experience I’d acquired while bumbling naively through the first part of my career. A key feature of the business structure is that Diagonal publishes everything in open-editions and nothing is signed or numbered.

-

JSWhy is it important that your editions remain open?

-

TAI wanted to remove the secondary market from the equation. People can always come directly to me to purchase the publications at the lowest prices, which are fixed – they only rise if the cost of materials demands it. And if I reproduce each piece indefinitely and there is no hierarchy in value created by signing or numbering, nobody can successfully resell these items at higher prices. Since buying from Diagonal is not a financial investment, one would only bother to purchase something if they valued the thing itself, which is the kind of straightforward exchange I’m after. I want people to own the Bragdon books I just re-published, for example, because I really just want them to experience his thinking. I'm trying to create the circumstances for a substantive, straightforward transaction.

-

JSIt must also give you the opportunity to expand your audience exponentially. I mean, what percent of the population feels comfortable walking into galleries, not to mention collecting art? Even I find it intimidating!

-

TAYes! I love being at the book fair and talking to everyone from design students to antiquarian booksellers to people who just came because it was something to do with their weekend.

-

JSSo, with something like the typefaces you design, you are making something that would typically fall under the umbrella of ‘design’ more than art, but I think it is actually one of your most personal projects. How do you make the fonts, and how are they supposed to exist in the world? What don't people understand about them?

-

TAThey just kind of happen along the way as a natural document of where my head is at a particular moment in time. It’s like the fonts are different voices, so Fig Font was the voice that narrated 2006 for me, or whenever I made it. When I was making a lot of woven paintings in the studio I found myself making a woven typeface, so Diagonal published a specimen of that, along with a group of woven-looking pins. Sometimes I make typefaces for friends who are musicians, and there is usually a connection between the structures of the letters and the structure of the music. I don't sell them as typeable fonts, just as specimens. I’m too emotionally attached to sell them for use. I once spotted a copy of one on a magazine cover and it felt like someone else’s lips were moving but my voice was coming out.

-

JSI like that. Our experience of the world is never fully separated from language, so the fonts are like a visualization of a complex moment in your life. Somehow beyond words, but rooted in them.

-

TAThey are indeed very personal but I didn’t expect that would register with anyone. Thanks for noticing!

-

JSWith what I would imagine is a rigorous production schedule, do you make things 'just for fun,’ or is that what Diagonal Press is for?

-

TAI’m not doing it just for fun, but fun actually figures in all of my work. For example, I recently developed a whole set of roller stamps, had them custom made and everything, and then I just did not enjoy using them. Loading the ink rollers was super messy, the best inks smell terrible, I just couldn’t find a way to enjoy working with them. So I abandoned that project. I didn’t think it would set me up to do good work, to be free in my imagination or fair in my thinking.

-

JSWell, it’s the cheesiest thing to say, but I have to do what I love, because I suck at everything else! This is why I stopped baking, I don’t paint and I stick to salad and photography…

-

TAI would like the net amount of joy in the world to increase, and I think art – or any object or image – transmits the energy of the maker, so I personally want joy to be a part of my process. I’m not saying that all art should follow this rule. And I am certainly tormented by my work on a very regular basis, despite my best efforts.

-

JSWell, at least you are trying! On the topic of trying to save the world, I am curious to know how you became vegan, what led up to that decision? It’s refreshing to meet someone who is not afraid to position this choice as a political one.

-

TAIt was something I thought about a lot over the course of fifteen years as a vegetarian. I agreed with the principles of veganism, but my absolute favourite food was cheese and I thought it would be too difficult to give it up. Then a few years ago a fashion house did something that caused me to take legal action against them – the details of which I won't get into – but as a result I received a settlement. I was faced with a dilemma, however, because I knew that a lot of this brand’s profit came from fur. So I decided to donate a large portion of my settlement to an animal welfare organization, but I didn’t know what to focus on or what forms of activism were most effective. So I did a lot of research. In the process I learned and saw so many things that I just can’t un-know and can’t un-see. I simply cannot enjoy a milk product, knowing what dairy cows experience. It’s not fun to me anymore. It’s not delicious. These products are a result of pain, it’s just that simple.

-

JSVegans get a bad rap for being a buzz kill, but the truth is out there, it’s just a matter of choosing to pay attention.

-

TAWell, it’s very hard to find the right, non-alienating way to talk about these topics. But this information is just as important for meat-eaters as it is for vegans! All I hope is that people take an honest look. My decision was not only one of compassion, but one of logic. Raising animals for food produces more greenhouse gas emissions than all forms of transportation, combined. Most of the land deforested in the Amazon is done so for raising cattle. There are a million damning facts and I could go on and on, but basically the industry is a disaster on all levels, and I can’t support it. After a lot of research I ended up funding two undercover investigations by Mercy For Animals, a group that embeds investigators in the biggest industrial farms to document and expose their practices. They shame companies like Walmart into changing their policies to be more humane, which I think it more impactful and pragmatic than trying to convince the whole world to go vegan.

-

JSAny tips for people looking to make the plunge to give up animal products?

-

TAI started by committing to it for just a month to see how I liked it and I highly recommend the experiment! And honestly, I wasn’t that optimistic about being able to stick with it, but I quickly felt much healthier and much happier because my behaviour was more aligned with my thinking. Maybe to answer your very first question, I think my life’s work is figuring out how to live in this surreal, fucked-up world in a way that’s both ethical and enjoyable. The circumstances of our time make that really difficult, so this is a life-long project. And it’s full of confusion. Sometimes it’s even harder to work out which is the right path than it is to get on it.

-

JSIf you weren't an artist, what would you be?

-

TAMy astronaut dreams are still intact.