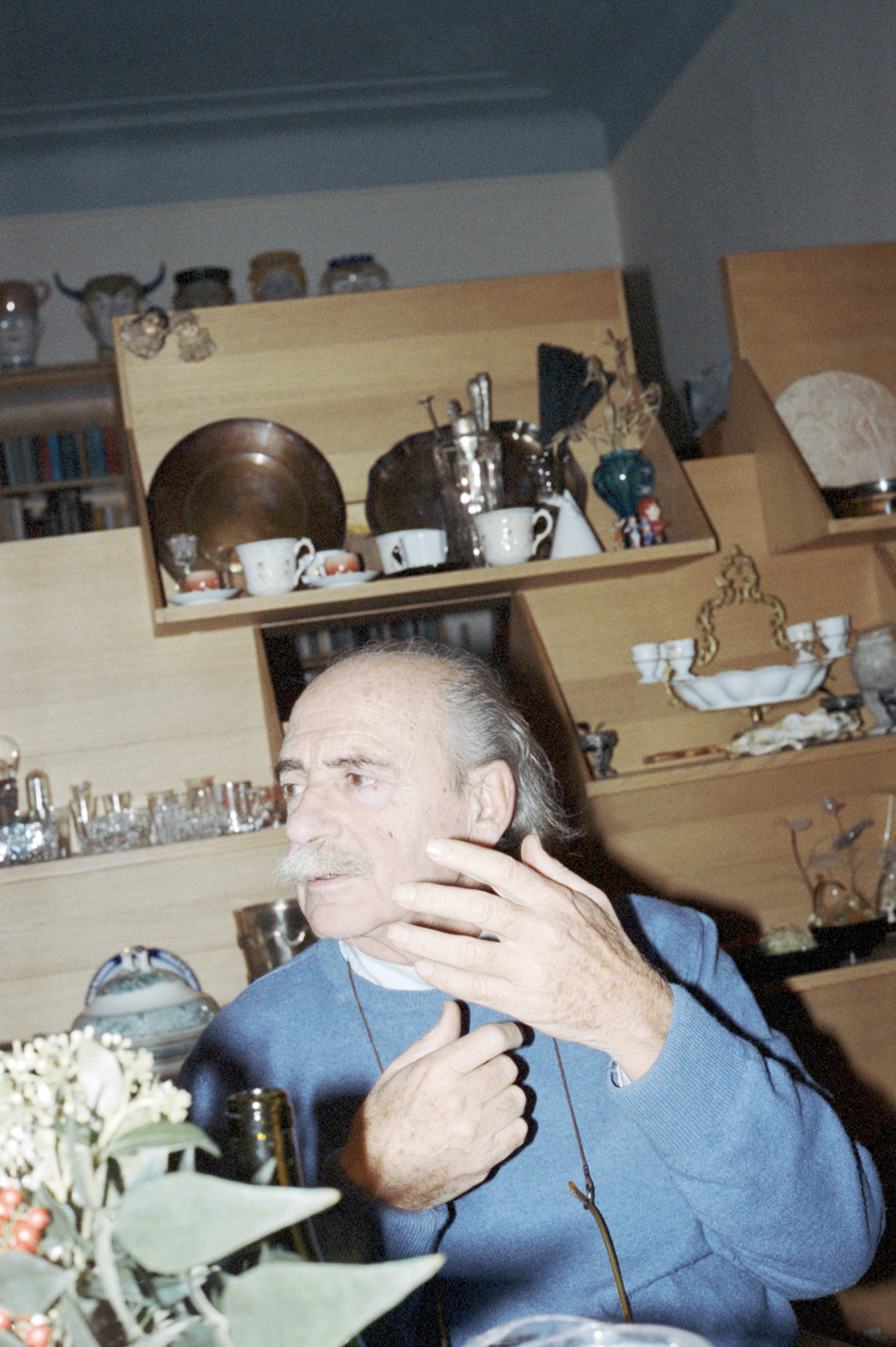

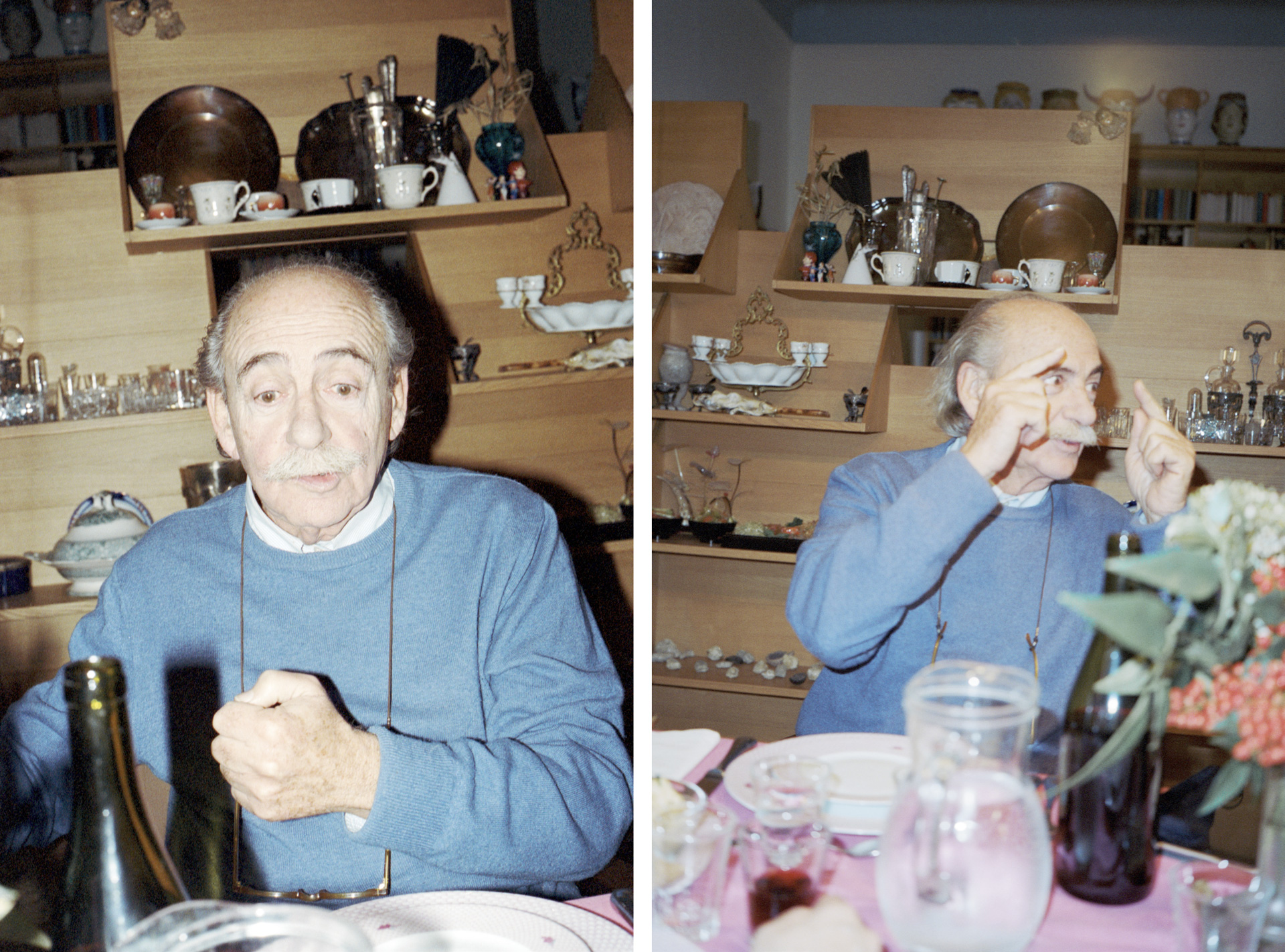

Dinner with Ugo La Pietra

At La Pietra’s house in Milan

Conversation with Federica Sala Photography Alessandro Furchino

-

ULPThis wine is called Ciliegiolo; it’s a wine from Liguria…

-

FSAh, yes I know Ciliegiolo, it’s delicious!

-

Sound of wine being poured

-

ULPNow Aurelia will get cross with me (pours the wine).

-

YDNI don’t drink red wine.

-

ULPWould you like some white? This white comes from one of my craftsmen, who owns a vineyard in Hungary and makes a very unique white. It has resinous bottom notes, like Greek wines, but it is exceptional! Because it seems sweet, then at a certain point this aroma emerges, a wonderful aftertaste… basically you’ve never tried a white like this! You still need to learn how to live: with just a bit of cash, 200 Euro, you set off. You go to Hungary and with another 100 Euro they’ll give you some land, half a hill. That’s what my craftsman did and he’s got a huge bit of land, he started cultivating grapes and now we have this wonderful wine. So have you tried it?

-

YDNNot yet.

-

ULPTry it, try it! You know what you’re talking about. And once you’ve tried it, tell me what you have to say!

-

YDN(tries the wine) Mmm, it’s aromatic!

-

ULPSo when you do an interview…

-

YDNWhenever we do an interview, it is always over a meal.

-

ULPIt’s just that Aurelia, who does a lot of cooking, didn’t have much time to prepare, so I hope you like it.

-

ALPUgo arranged the glasses though (sarcastic tone)

-

ULPThere we go, I knew it…

-

FSShe said that earlier, she said you’d laugh at how he arranged the glasses!

-

Laughter

-

ULPLet’s talk about you, about us now. What shall we talk about?

-

FSThe exhibition at the Triennale, seeing as it’s an exhibition that spans your entire career… let’s take that as an insight into your way of seeing things.

-

ULPOk. But are you interested in talking to me as a person, as an artist, as a person of the world, as a dining companion or as someone who knows everything there is to know about eating?

-

YDNOh do you know everything there is to know about eating?

-

ULPWell I cook a lot… in all senses. If I have one skill that has finally been recognised in this exhibition, it’s that in the last 35 years I have cultivated what I call territorial design. That is to say, design linked to genius loci, the value of an area. I have always condemned those who are all “made in Italy made in Italy made in Italy”, which means absolutely nothing. Parmesan is not made in Italy, it is made in Reggio; capers are not made in Italy, capers are from Lipari. And the same goes for our design, our design is connected to our territorial, historical, mythological and social values and so on. So it is therefore connected to genius loci, which exists in every nook and cranny of our area and is our true value.

-

FSThis is the value of everyday life, of history…

-

ULPI have tried to do this design work, not just theoretically but by creating collections of objects, from Caltagirone to Udine. And since I am somebody who has loved and theorised this reality, I naturally cannot forget that the same goes for the objects that add value to our great tradition of the Mediterranean diet, in other words, the diversity of our foodstuffs. The Mediterranean diet is made of these products that are connected to the various genius loci, but the basis of which is this (indicates the table). This is the Mediterranean diet.

-

ALPThe primary value of the Mediterranean diet is conviviality.

-

FSAnd the second is diversity.

-

ULPExactly, diversity. And this stands for what I have always claimed in the world of design. In the Sixties, we opposed the internationalist design theorised by some architects. Before anyone ever heard the word ‘globalisation’, we used the word ‘internationalist’ but we opposed anybody who designed the same house in Zurich, Palermo, Cairo and Tokyo. Think that just 30 years ago, when I was working on my so-called territorial projects and making objects with craftsmen, I was a poor wretch because the world…

-

FSBecause it was the century of industry, the industrial world, moulds…

-

ULPThe industrial design world claimed that things made by craftsmen were kitsch and had no value. Now 30 years later, everyone’s talking about craftsmanship and the word ‘industrial’ has almost become taboo.

-

FSYou can’t even graduate in industrial design at the Polytechnic anymore, they’ve discontinued it…

-

ULPThey’ve discontinued industrial design, because it’s become an embarrassing term to use.

-

FSTrends and their extremes come and go in all parts of life: nowadays industry represents pollution.

-

ULPFor example, the relationship between nature and architecture is very trendy nowadays and nobody seems to understand that nature always beats architecture hands down. So this relationship with nature must be very delicate.

-

FSWell there is a macro and micro relationship between architecture and nature, I really like looking at the facades of houses when I’m out on my bike. I like seeing if a house is loved or not.

-

ULPYes, you can tell, from the balcony for example…

-

FSExactly, you think: that person loves their house, that person doesn’t, that person might do…

-

ULPI do that a lot as well.

-

FSI find it very sad when I see a place that I really like, that I feel drawn to, and I see that it is not very well loved. But it’s ok when you see something you like and see that it is loved, even if it is loved by somebody else.

-

ULPIn the Seventies, there was a space between two buildings in a neighbourhood in Berlin and I used it to make a shared greenhouse with lots of pots. Everybody had their own pot with their name on and we made this greenhouse, which was a collective object although everyone had their own role within it. It was about involving people to work together.

-

ALPAre you not eating (addressing the photographer)?

-

AFAh yes, I’ll have some now.

-

ULPGreen space is always treated badly. I am doing an exhibition at the moment that is called Il Verde Resolve (The Green Solution): when you have bad architecture, you just add a bit of green and it resolves everything. When you’ve got bins outside your house and don’t know how to hide them, just put a bit of green in front of them and problem solved. When furnishing a house: “We haven’t decided what to put in that corner yet, something is missing (clicks fingers): a fig tree will solve the problem!”

-

Laughter

-

ULPEverything is almost always solved with a bit of green. Poor old green, once the home of nymphs, elves and genius loci - it was the most spiritual place in the world, the divinities lived inside it, didn’t they? Now it’s become a material used to cover up the blemishes created by uneducated and underprepared professionals.

-

YDNWhereas in the magazine world, it’s paper that solves all problems. Porous paper makes photos look better.

-

Laughter

-

ULPDamn you and your porous paper! For some time I’ve let myself be seduced by porous paper as well, “Ah! Porous paper…” And in fact, when I saw the magazine, “Ah! Porous paper…”

-

Laughter

-

FSWhere is the green exhibition being held?

-

ULPIt’s in a beautiful gallery in Busto Arsizio, called Il Chiostro. A wonderful gallery that I discovered a few years ago during a collective exhibition. There are already two of my pieces on the forest in the Triennale, in anticipation of this theme. For me, green was a way to overcome the fracture between the conceptuality of the Sixties and Seventies and the showiness of the Eighties. For me the garden resolved this fracture, there I can use the two values harmoniously. Just think of a labyrinth: the classic example of a showy yet conceptual object. There is an area dedicated to the garden on display at the Triennale, where I have re-examined a few projects such as Milan’s organic vegetable garden and Palermo’s too and urban parks in Bologna and Rome. There is also another piece of mine in the Triennale about how the bench is a means with which we can decodify the urban setting…

-

FSI think you should take on a semantics project at some point. Because your projects have often then become terms that didn’t exist before. All your work on spontaneous green was a precursor to guerrilla gardening. You really anticipated the whole thing about the relationship between the individual and the collective within a city and elements of the city, whether green space or urban furnishing. The synaesthesia of the arts today has become the transversal nature of the arts. These are things we hear about every single day nowadays…

-

YDNYou recently collaborated with the brand Loewe.

-

ULPI didn’t know of it beforehand, then I heard about this big company whose creative director was interested in genius loci and so when they called me to do their shop in Milan, I accepted.

-

ALPEat up before it gets cold.

-

AFWhat is it?

-

ALPPumpkin and sausage risotto, it needs cheese though.

-

ULPHere it is, anybody want some cheese? To return to the exhibition, houses are often very similar but you will have seen some research that contradicts this theme; I did some photographic research that investigated the use of the object in houses through interviews with a very diverse range of people: a labourer, an office worker and so on. In the Sixties and Seventies, people had a very differentiated vision of what desire for an object could be, because so many of them lived in such diverse conditions…

-

ALPDo you want the cheese down there?

-

YDNNo thank you, it’s already delicious.

-

ULPLet’s say that the labourer has her mountain hut and very modest, or even non-existent, reference parameters, while the office worker has his office and sees the office of his boss, of the company president etc. and yearns for those models. Now, which models do we each see? They are all the same. That is to say, the model that might influence us in some way, through magazines or television, is an image model that belongs to everybody. But when I interviewed the lady who lived alone in the mountain, I asked her “what do you want?” and she replied, “nothing, I already have everything”. Desire for objects is directly proportional to the type of life that a person leads, which at the time was very diversified because somebody who had emigrated, done 20 years in the mines, seen nothing and then gone back to their country and built a house, had no reference parameters. They built horrible things but they were very diverse. Nowadays, everybody has more or less the same types of influences. And so it is much easier to find common denominators that did not exist then.

-

AFI’ve seen the exhibition you’re talking about…

-

ALPYes, where the lady says she would like to have a radiator but she has no central heating…

-

FSYes, because the advent of modernity came at some point and the ‘new’, irrelevant of what it was, was indiscriminately better than the ‘old’.

-

ULPIn the Sixties, a piece of wooden furniture was absolutely unthinkable, everything had to be resin washed or made of plastic; it was like wearing long skirts when everybody was wearing mini-skirts. You just didn’t do it. So there were these so- called stylistic fashions, which all came in the early Eighties. And if you’ve seen my exhibition, there is that moment where I tackle the theme of time and memory in contemporary society through the online house. In the Eighties, memory changed: it changed from three-dimensional to two- dimensional. Neo-eclecticism was born in the early Eighties with this opportunity to access all the available images thanks to the increase in IT and telematics. This was the great revolution. Then many other theories and research was based on this, in the early Eighties, official culture was still connected to certain traditions, just think about the trend for post modernism: the umpteenth stylistic indication that was proposed in the spirit of archaism and still did not look to the future, which was neo- eclecticism.

-

AFAnd what were the Nineties for you? ULP During the Nineties, we entered this tunnel that we still haven’t emerged from. There haven’t been any other movements of hope or enthusiasm.

-

FSMaybe, but the new economy and the dawn of the internet and digital in the Nineties brought plenty of enthusiasm... ULP In ’72, I did a project at the MOMA which clearly predicted the use of the internet. It was a contemporary version of the old lady sitting outside on her porch on village streets. The fact that the city never communicates, it never talks, and it’s only the balconies that summarise all the knowledge, invention and desire to leave your own house, means that the relationship between internal and external is never cultivated, if not at these microscopic levels.

-

The table is cleared

-

ULPIt is truly a disgrace that we cannot even begin to imagine that a city could talk in some way, tell us what it has done, what has happened, with circumstances, outside and inside. Communication in terms of internet has also developed at an exaggerated rate, but communication as our tool has still not brought this dimension into play at all. We’ll call this dimension “inside-outside”. The only true communication we have in the city – and this is another chapter which I held a really good course on in Venice -, true communication, the people who make the city, who make the image of the city, are the anonymous personalities, creatives mind, very important people, who we know as window dressers. You realise that the image of a city is made by shop windows. For years, wherever I went, I only photographed shop windows. And I showed, it is easy to show, that it is not the architects or designers or artists who make a city: it is shop owners.

-

YDNSorry, is this cavoliceddi? What are they called here?

-

ALPRapini.

-

ULPThe ones with flowers, the top part of the rapini. They look a bit like brussel sprouts, don’t they?

-

ALPWell they are part of the cauliflower family…

-

YDNI’m not really sure what cavoliceddi are, I’ve always known them by that name and in Sicily they cook it with sun-dried tomatoes and sausage.

-

ALPOk, I see. But is it not the same?

-

YDNYes, I think it is this.

-

FSThe dates show that you were ahead of the times in some way…

-

ULPBut the things I did were never done in the knowledge that I was ahead of the times. I saw that 80% of furniture production was classic or period and was instantly condemned by the industrial design world as something deplorable, something negative. But I realised that within it was this culture of making that was kept alive, because there were still people who could make mosaics or glass in a certain way. I used to get angry at the design world, which in a certain way hid and disregarded this other world.

-

ALPDo you sell those plates there?

-

ULPI didn’t want to do the Triennale exhibition, I didn’t like it and I didn’t think it was the right thing. It was a friend who convinced me to do it and I’m happy they did because I was pleased with it.

-

FSWhy didn’t you want to do it?

-

ULPBecause my work has always been against the system: among the architects I wasn’t an architect, among the designers I wasn’t a designer, among the artists I wasn’t even an artist… So I was always a bit out of place. I have always worked deep down, on underground things. I couldn’t be too exposed because the type of things I did constantly contradicted the official world. I may have worked for over 30 years in the world of craftsmen, but I concealed that fact.

-

FSAnd now with this phenomenon of the return of craftsmanship…

-

ULPNow anybody who works with craftsmen is on trend. A bit like when I was alternative in the Seventies, in a society that was almost completely alternative. The drama came when, in the Eighties and Nineties, I did some work with craftsmen when Italian industrial design was still Made in Italy: it was all experienced in such a way that I couldn’t even pronounce the word craftsmanship. So much so that I coined a lot of terms to try…

-

FSAh yes! “Fatto ad arte”?

-

ULPFatto ad arte.

-

FSBecause craftsmen were one of those things you had to get rid of or hide, like your granny…

-

ULPExactly. You understand that when somebody wants to ask and wants to understand my work but looks to me as the radical, the unbalanced one… It is hard to explain that one of the most unbalancing things I have ever done was work with craftsmen to make the hundreds of objects I have made in the past 30 years.

-

FSIt is difficult to understand because it is something so current nowadays and you need to really understand the dates and the values of the time in-between to really understand… Perhaps we should ask, while Ugo La Pietra was doing this, what were the others doing? Or perhaps we should concentrate on the present to see the future? What is Ugo La Pietra doing now?

-

ULPYou ask me what I see in the future. I would like there to be someone working for collective, urban space. There are architects that spend all day thinking about architecture and skyscrapers, designers that make objects from dawn till dusk, artists who work for museums… but who works for the city? Nobody, absolutely nobody. We need the contribution of people who work in various disciplines in order to achieve a place that is usable and enjoyable. In the Seventies, people began talking about a discipline called “social artistry” which is different from the artist making pieces for museums and taking them into the town squares. That doesn’t…

-

FS…trigger a social mechanism.

-

ULPExactly, that never came about. There was support and initial attempts in the Seventies, groups of people who felt that need. This is what social artistry needs to do: it shouldn’t make urban interventions; it should intervene to elevate the population to the right levels of awareness. If you ask people what they want in the city, they’ll tell you they want more plants, more green space… They want plants all over the place, but that is not the solution to our problems. So the task facing social artistry is to be art that approaches this social work in order to raise it to a level of awareness where they can then propose genuinely valid and fundamental projects.

-

ALPDoes anybody want a coffee?

-

ULPYes, everybody I think.